Longtime Berry Researcher Finishes His Academic Career on a Sweet Note

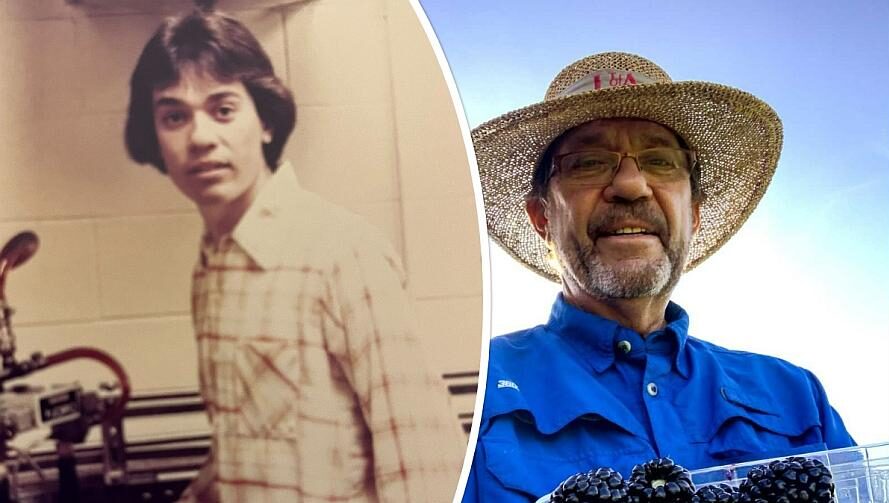

[John R. Clark — then and now] Berry scientists have many career options today. When I received my Ph.D., the only choices were working for universities or USDA-ARS. Many of my students now lead major private efforts in the berry industry.

I finished up this fabulous university career at the end of 2022 and want to share a few reflections on the berry industry, berry research and development, and the evolution of both over time.

1. The expansion of berry crop production and availability.

Forty years ago, other than strawberries, our other three major berries were only found seasonally (if at all) in grocery stores. In the mid-1990s, I remember seeing my first grocery store blackberries imported from Chile. Look at how far we have come. All four berries can now be found in continuous supply in retail markets! Plus, local markets are much more expanded for all berries. Why did this come about? There are many factors, but a few key reasons include expansion of adapted varieties (and growing methods) for a wider production area, plus huge expansion in production coupled with expanded marketing.

Reported health benefits of berries and profitability in the berry sector ultimately drove expansion, too. A number of positive factors have led to where we are today in the berry industries, and consumers enjoy huge benefits.

2. Genetic advancement with new varieties.

Forty years ago, most of the blueberries were grown in high-chill areas and were mainly of the northern highbush type. With the exception of California and Florida, strawberries were all matted-row varieties. Processing blackberry was a major industry in Oregon, but the remainder of the country had mostly local production of thorny varieties. Raspberries were primarily a local-market crop, with much of the country not familiar with this crop. Today varieties exist with much wider adaptation. A prime example is blueberries, with low-chill varieties contributing to a huge production expansion. Genetic advances across berry crops continue to occur at a fast pace, with unbelievable advances in areas of adaptation, firmness, flavor, season of ripening, postharvest storage potential, and many other traits. Times are good in berry breeding!

3. The origin of varieties has shifted.

In 1980, almost all berry varieties originated from public sources (e.g., USDA-ARS and universities). This was true in other countries as well. Today we have major varieties of all berry crops originating from private breeding programs, and this shift is accelerating. Berry crops and other specialty crops are catching up with row crops and vegetables in that private breeding is becoming very important. A key reason is that the berry industries are now large enough to provide profit potential for long and expensive breeding investments. Additionally, major changes have occurred in many public institutions, where variety development has been abandoned or shifted to molecular breeding research. Public programs continue to be important for all berry crops, but they now share the variety stage with numerous private developments. The good news for growers is that the diversity of private programs helps ensure there will continue to be a strong variety supply, although private developments are not always as widely available to diverse growers compared to public, unrestricted developments.

4. Berry scientists have expanded career options.

When I completed a Ph.D., the only opportunities were with universities or USDA-ARS. Today a large number of plant breeding/genetics graduates pursue private-sector careers, even in the berry space. In fact, I have several former students who lead major private efforts, and their accomplishments are impressive. They enjoy the opportunity to focus on variety development without the challenges associated with publishing, grant attainment, and teaching responsibilities that come with university jobs. Thankfully, we have many outstanding public breeders that continue the rich tradition of public breeding, plus training the next generation of breeders. We have to have these folks, and it is critical to support universities to provide this training!

It has been a joy to be involved with the development of the berry industry. What’s next for me? Surely there is a berry activity in the future somewhere … it seems too much fun to let it go!

Let the berry good times roll!