How the California Grape Industry Is Coping With Water Woes

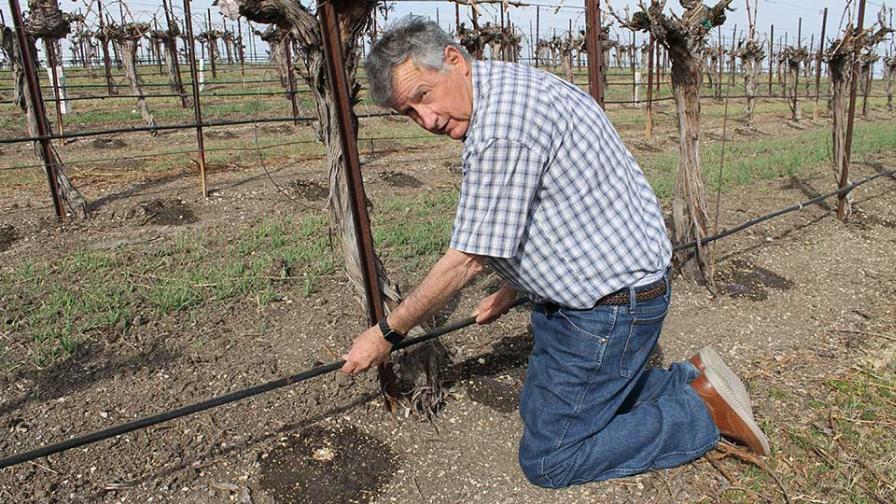

Paso Robles wine grape grower Dana Merrill has been branded a troublemaker for constantly speaking up at public hearings for wine grape growers, but he doesn’t mind, and he hopes other growers in the region are willing to work in the future for a secure water supply.

Photo by David Eddy

When Dana Merrill first got a look at Paso Robles, a town about 25 miles inland from the Central California coast, he didn’t think much of it. “Paso Robles was a cute, small town with historical charm; but there really wasn’t much going on to drive the economy, create jobs, and keep future generations here,” he says. “That’s the charitable way to put it.”

But he had arrived at the right time, as the area was at that time rapidly becoming known, with its not-too-fertile soils and wide diurnal temperature swings — both critical for producing premium wine grapes — as a great place to grow.

“This place was reborn with the wine grape business,” says Merrill, who founded his wide-ranging consulting business, Mesa Vineyard Management, in 1989. “By the late ’80s, it had really started to transform into something special.”

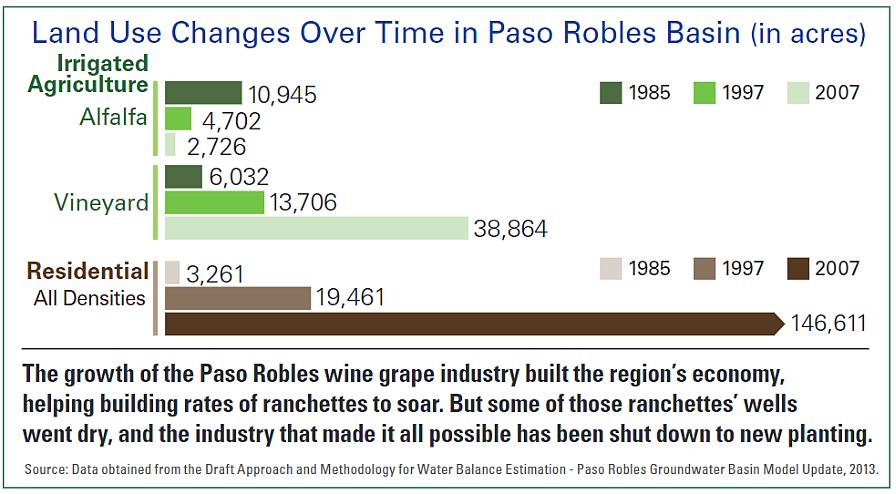

But for nearly a decade, the industry, which is completely dependent on ground water, has ceased to grow for lack of water. In 2013, the County Board of Supervisors determined that the Paso Robles Basin, which extends far beyond city borders and has a large aquifer beneath, was being over-pumped, and it passed an ordinance banning new irrigated lands.

Golden State Sizzles

Of course, Merrill and his fellow Paso Robles growers aren’t the only ones in California to have problems, as a lousy snowpack from the winter and an unusually warm spring are already causing problems this season. California’s farms and cities that draw drinking and irrigation water from California’s major rivers were ordered in March to prepare for mandatory cutbacks. The State Water Resources Control Board announced it was sending letters to approximately 20,000 water right holders — farmers and cities with historical legal claims to river water.

They were told to expect to stop pulling water in the coming weeks — and even earlier than last year. It wasn’t until last August 2021 that the water board ordered thousands of water users to cut their water use on the Sacramento and San Joaquin River watersheds — arguably the two most important rivers in the state. The fact that the board issued a warning in March about similar curtailment orders is a sign of the deepening severity of the drought.

“We are experiencing historic dry conditions: February is usually California’s wettest month, but January and February 2022 were the driest we’ve seen in recorded history,” the letter reads. “Statewide, precipitation is less than half the yearly average, and dry conditions are forecast to continue through spring. Last year, extreme drought conditions led to unprecedented actions by the State Water Board that included curtailment of water rights in many California watersheds.”

The letter is directed to water rights holders across much of California. Like last year, the state warned those who pull water from the waterways that feed into the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to expect cuts. That affects a massive swath of the state — from Mount Shasta to Modesto to Bakersfield — due to the various tributaries that flow into the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.

Wine Industry Flourishes

But the situation in Paso Robles is vastly different, as growers in the Central Coast region don’t have access to such rivers or government projects. It is painfully frustrating Merrill, who was there to see the industry take off.

As a young man, he started farming just to the south in Santa Barbara County, growing sugar beets, flowers, and anything else he could get a loan to plant, as money started drying up in the 1980s. He took a job as a foreman with McCarthy Farming, which was growing grapes under contract for a lot of the big wineries, and learned to grow wine grapes.

“It turns out I got involved in the wine business — I didn’t know it at the time — right when the Central Coast wine business was starting to take off. But there wasn’t much going on here. Eberle and Justin (wineries) had just started, and there were maybe six wineries.”

However, county planners were still friendly to the industry at that time, and Merrill says they were smart enough to put few restrictions on the wineries, other than you had to have enough acres.

“There were very supportive,” he says. “You could basically put up a winery anywhere on ag land.”

But with wine and fine food going hand in hand, the wineries brought with them fine restaurants. Paso Robles got its first French restaurant, and once more winemakers started coming to the promising region, more chefs and restaurants followed. Weekenders descended from Los Angeles.

“It turns out people discovered this place as a nice place to live,” he says.

Today, the industry is the top economic driver for the entire North San Luis Obispo County region. It has more than 200 wineries, most of them quite small, but there are a number of world-renown brands.

“We also sell a lot of grapes to North Coast [(Napa, Sonoma, etc.)] wineries,” Merrill says. “They may even be fermented here and then taken north to bottle.”

Focus On Growing

Mesa Vineyard Management Services now bottles a small amount of grapes at their own winery, but that is more of a side business. Merrill says they farm 400 acres of their own grapes, and sell 98% of what they grow, because farming wine grapes is what they know best.

They manage a total of 13,000 acres and are one of the few wine grape management firms to work in multiple counties, as Merrill says there are only three or four such firms left in the state. Mesa manages vineyards as far north as Southern Oregon and as far south as Santa Barbara, although they don’t consult on the North Coast. They manage vineyards for wineries, investment companies, and private growers.

For a long time there was a surplus of water. “The only saving grace here is that it is a huge aquifer — though even though it has dropped with more dry years, more people and more crops — it’s still a massive aquifer,” Merrill says.

While the county may have planned well for wine grapes, they didn’t do so well with residential lots. There were paper-lot subdivisions of one-acre lots throughout the region. In the 1970s, when people really started fleeing the Los Angeles area, Merrill says contractors figured out they could put a lot on an acre and sell it for $50,000.

“Put in a 200-foot well, and you’re in business. There are hundreds upon thousands of these homes. They put them all over the place. People end up living among agriculture and they really like it, but when they start running out of water, that’s when the politicians get nervous,” he says. “They were like ‘These people are really mad.’ To survive, they panicked and passed the ban on new irrigated lands.”

Merrill does all he can to save nature’s most precious resource. He generally uses two emitters per vine, and has gone down to rates as low as just a half-gallon per hour in some areas, trying to reduce the input rate for the soil to make sure not a drop is running off.

Photo by David Eddy

The ban remains in place, as there is still over-pumping of the basin to the tune of about 78,000 acre-feet per year. That’s 13,000 more than the 65,000 that models show can be safely pumped annually. Growers can’t plant on new land; they can only replace a crop with a less-thirsty crop. Historically, the land was used as pasture, and farmers grew mainly alfalfa, a very thirsty crop that has largely been supplanted by wine grapes.

“We’re at 35,000 estimated wine grape acres, and not many alfalfa acres are left. Far and away the largest irrigated crop is grapes, which is good news and bad news,” Merrill says. “The bad news is grapes only use an acre foot to about an acre foot and a half, they are all on drip. – But you can’t switch from alfalfa to grapes anymore because it already is grapes. The good news is that 13,000 acre-feet of water is not that much water. It’s an eminently solvable problem.”

What’s Next?

There are several sources of water that have been identified over the past 50 years, but nobody has made the move to use them, Merrill says. San Luis Obispo Country could access the State Water Project, which comes through the county in an aqueduct on its way to Santa Barbara County and points south.

Growers are saving all the water they can for the most part, he says. He generally uses two emitters per vine — and has gone down to rates as low as just a half-gallon per hour in some areas — trying to reduce the input rate for the soil to make sure not a drop is running off. Technology offers a chance for more progress, or course.

Now the state is requiring management plans for all groundwater basins as part of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, so Merrill thinks Paso Robles needs to get started on some sort of plan to get more water to keep the region’s economic engine oiled instead of fallowing productive farm land. Local leaders need to act, and act now.

“The state might say get rid of irrigated ag and stop building houses if we’re not coming up with something,” he says, adding that he’s worn out from being branded a trouble-maker for constantly raising the issue with county leaders. “They all think everyone else is going to solve it, but I don’t think anyone is doing enough to meet the dual challenge of regulation and drought.”