Welcome to the Age of Digital Agriculture

Growers have traditionally relied on scouts to get the information they need to make decisions. But there are a couple of problems with that. First, the data gathered isn’t always 100% reliable. Second, labor costs are rising – that is, if growers can even source the increasingly scarce labor they need.

Researchers at the Digital Agriculture Laboratory at the University of California, Davis, are trying to change that. Dr. Alireza Pourreza, a University of California Cooperative Education Specialist of Agricultural Mechanization, is leading a project to employ remote sensing for nutrient content detection in table grapes.

Growers have certainly seen some of this technology before, usually by companies eager to provide a service. But the goal of this project, says Pourreza, is to develop a decision-support tool that enables growers to automatically process and analyze the aerial imagery that they can obtain themselves by flying a drone equipped with a multispectral camera, and then make decisions based on that interpreted data.

It’s not that dealing with aerial data doesn’t require some kind of expertise. Pourreza says if you don’t have this expertise, you may not do it correctly. There are a lot of tricks you need to know to realize, for instance, that bad data is getting in. A lot of people don’t complete all the necessary steps required for a radiometric calibration of aerial spectral imagery. But that would all be taken care of if Pourreza and his team are successful in implementing the automated web-based aerial image processing and analytics pipeline that employs cloud computing and artificial intelligence – machine learning in particular – to convert raw data into actionable knowledge.

“Just looking at all those pictures takes a lot of time. Computers can do it many times faster,” he says. “Eventually we will make those models available on our website. Growers will be able to access these models, which will allow them to make sense of their data.”

Pourreza hastens to add this is not about “farming a laboratory,” as doubters of precision agriculture sometimes say about aerial data.

“Everything has to be ground-truthed,” he says. “Collecting ground-truth data is expensive, but collaboration with plant scientists at UC-Davis makes it less expensive to generate large libraries of ground-truthed data that is required to accurately calibrate models.”

Growers won’t need to get involved in the complex procedure of data processing and analytics if they want to use drone-based vineyard monitoring.

“We are trying to make this like an automated pipeline of data, then enclose that in a box. Growers don’t need to know what happens in the box,” he says. “Just input the data and, at other end of the box, get an insight map. Then you make the decision.”

DON’T GO WITH YOUR GUT

There’s an old saying that farming is half science, half art. But don’t tell that to Pourreza, who will tell you that it’s all science, all the time.

“An efficient food production system depends on an accurate and timely decision-making process. Agriculture is often not an efficient system, many decisions are made on gut feeling, because either there is no data, or there is no reliable interpretation model,” he says. “More data means more accuracy – always. It’s all about the data.”

Pourreza says that, with accurate data from the field, we can improve our decision-making and be more efficient. An efficient system will take care of all in-field variabilities, minimize waste, and generate uniform yield and quality throughout your entire vineyard or orchard.

“Soil type is hard to change, and variability in soil is hard to manage,” he says. “But variabilities due to a disease, an irrigation problem, a nutrition deficiency? We can get rid of those by adopting data-driven crop production management, and we can improve our yield.”

However, you can’t manage what you can’t measure, and obtaining high-spatial resolution data from the field is not easy. Growers have traditionally relied on scouting but in recent years have run into a serious lack of labor. It’s one reason crops that can be mechanically farmed for the most part have become so popular, especially in California.

“That’s why so many vegetable fields have been replaced by nut orchards,” he says. “But scouting all those acres is time-consuming and can be subjective.”

“Subjective,” like “art,” is not a word Pourreza thinks has a place in farming. It should be all about the data. “Answering all questions requires data, that’s what it’s all about,” he says. “We think farming decisions based on any data are better than decisions based on no data.”

BEYOND PRECISION

Best of all are decisions made based on vast amounts of data; what Pourreza calls “digital agriculture.” But isn’t that what precision agriculture is all about?

“Digital ag is the next level of precision ag,” Pourreza explains. “It uses a lot of similar concepts, but it’s mostly focused on data. Digital ag is getting so big, we can think of it as being different.”

When Pourreza is talking a lot of data, he’s not kidding.

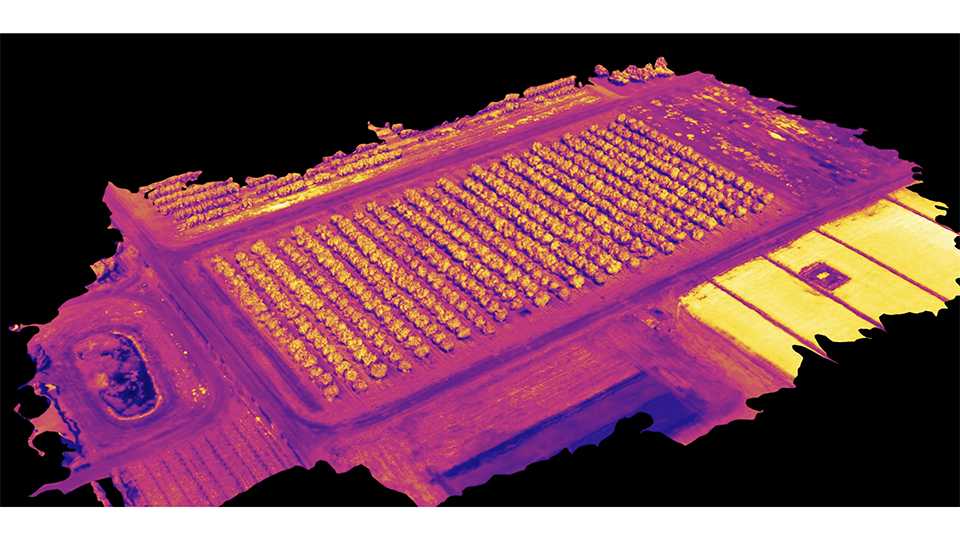

To get enough data for such a feat – essentially checking on the health of a vineyard without setting foot in it – requires some advanced equipment. The drone used in the table grape vineyard trial is an Enterprise UAS DJI Matrice 210, which can carry up to about 15 pounds while equipped with multispectral and RGB cameras.

“What we are proposing is flying the drone about 20 to 30 minutes to do 50 to 80 acres. One flight for geometry, one flight spectral, then we fuse them together,” he says. “Eventually we will have nutrient content information for each vine. This is something new.”

Pourreza says there is some software available that can tell, for instance, where missing trees are. But there is a lack of interpretation models that are accurately calibrated and customized for monitoring specialty crops in California. That’s what he and his colleagues have been working on.

“At the Digital Ag Lab, we are trying to find out the optimum way for growers to collect data,” he says. “This is something growers can do themselves.”

As with most advances in technology, the process is going to get easier for growers, not to mention cheaper. Pourreza says that today growers can get a decent drone that includes an RGB camera and a multispectral camera for just $6,000 to $7,000.

“I think the growth of drones (in permanent crops) will be exponential as soon as growers see some value in them,” he says. “If they see they know much more this year than last year when they weren’t using them, then they will catch on.”

YOU MAKE THE CALL

Of course, growers can currently buy a drone and collect aerial images. Just the ability to look at the field from above will give you some insight. But soon, Pourreza says, growers will be able to learn so much more.

For example, we can see if a grape leaf changes color in visible range, but if there are any changes in non-visible colors, such as near-infrared, your eyes will not be able to see that, he says. You need multispectral cameras to monitor plants in non-visible bands and computer models to objectively tell you what each color means. Today you would need to collect sample leaves and send them for laboratory analysis to understand, for instance, vine nutrient status.

However, with digital agriculture you can get more than what you see in a simple image.

“You’re looking at colors, true, but not necessarily ones you can see. With multispectral cameras, we can measure reflectance of vegetation in non-visible bands such as near-infrared,” he says. “We can see what people with their eyes can’t see, and that’s very good information.”

Digital ag is all about gathering vast amounts of information, much more than is currently done. It’s also about synthesizing that data so that it will be usable for growers.

What it’s not about, Pourreza emphasizes, is removing growers from the decision-making process. “We are not trying to make decisions – or even replace humans with machines – we are just trying to give growers better insights into their vineyards,” he says. “They’re making the final call.”

Other Digital Ag Projects

Grapes aren’t the only fruit or nut crops Dr. Pourreza and his colleagues at the Digital Agriculture Laboratory at the University of California, Davis, are focusing on.

Pourreza says they are working on yield forecasting in an Almond Board of California project. Yield is correlated with canopy sunlight interception, and currently researchers have to rely on readings from a light-bar unit that you attach to an all-terrain vehicle. But you can only run the unit at solar noon, the exact point the sun is above, which is actually closer to 1 p.m. Pourreza and his team seek an aerial solution to replace the light bar. By using aerial imaging, images can be captured at any time, not just at solar noon.

“It’s a big advantage – if it’s overcast, for example,” he says. “It’s important that we can fly any time we want.”

Another aerial imaging project at the digital ag lab is in walnuts, detecting impact of soil-borne pathogens such as nematode stress. Researchers planted different genotypes inoculated with various level of nematodes and are using high-throughput phenotyping techniques such as proximity and remote sensing to track plants’ responses to the imposed stress.

For more on the lab, Pourreza says they are active on Twitter: https://twitter.com/DigitalAg_ucd.