What Controls Downy Mildew in Cucumbers – and What Doesn’t?

The cucumbers ‘Speedway’ (front) and ‘Bristol’ (back) in non-trellised plots with foliage yellowing due to downy mildew on June 23, 2017. Photo by Anthony P. Keinath

With downy mildew so widespread, I and other researchers from Clemson University wanted to find the best cultural practices to control the disease. Currently, growers apply weekly fungicide sprays to prevent yield losses. Are there more effective practices?

To find the answer, we studied three areas: cultivar selection, fungicide use, and trellising. We also wanted to know if combining the three management practices was better than combinations of any two practices.

Fungicides Control Downy Mildew Best

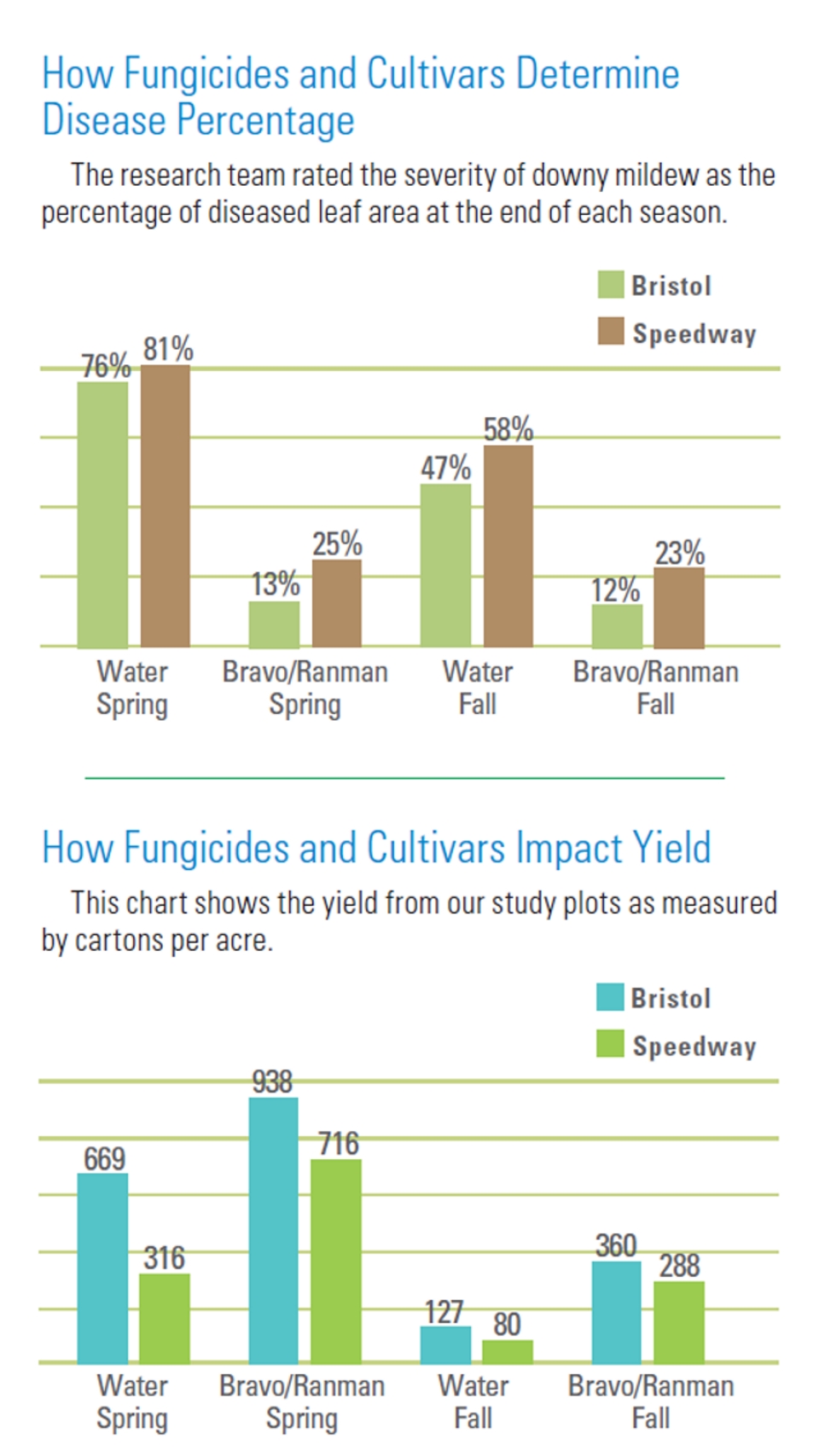

We learned that fungicides had the largest impact on reducing disease and increasing yield. In both seasons, fungicides were the only factor that affected percent cull fruit (misshapen) — 16% versus control plots (27%).

Without fungicides, growers would have lost $980 per acre with ‘Bristol’ and $1,915 per acre with ‘Speedway’ in the fall.

Cultivar Choice Matters, Too

For cultivars, we wanted to address a challenge that stems from genetics. Older cucumber cultivars with resistance to the A2 mating type of downy mildew (a.k.a. the squash strain) are susceptible to the A1 mating type (a.k.a. the cucumber strain).

Cucumber cultivars with a new source of resistance to downy mildew caused by the A1 mating type have hit the market.

We selected one of these new varieties, the partially resistant ‘Bristol,’ released by Bayer in 2017, for our research. How well would it perform when treated with a low-cost fungicide program, one that’s normally only moderately effective against downy mildew?

Downy mildew resistance in ‘Bristol’ reduced disease ratings during the growing season and mostly held up until the end of the season.

As expected, it had less severe downy mildew than ‘Speedway.’ Combining ‘Bristol’ with fungicides was especially effective, as this treatment always had the least severe disease.

Interestingly, we found using a resistant variety increased yields in the spring but not in the fall.

In the spring, ‘Bristol’ yielded more fruit than ‘Speedway,’ regardless of whether the cultivars were sprayed or not. In fact, the yield of ‘Bristol’ without fungicides was the same as the yield of ‘Speedway’ with fungicides.

Although we did not see a yield benefit of choosing ‘Bristol’ in the fall, its improved disease resistance and vigor make it a good cultivar for either season in the Southeastern U. S.

‘Bristol’ was a vigorous cultivar with longer vines than ‘Speedway.’ At 45 days after seeding, ‘Bristol’ vines measured 65 inches, while ‘Speedway’ vines were 51 inches. Although we measured vines only in non-trellised plots, ‘Bristol’ vines in trellised plots appeared to be longer.

I should note that yields were lower in the fall than in the spring overall, when about a half to a quarter as many fruit were harvested. We took this into account when assessing results between the two cultivars.

These results suggest that ‘Bristol’ might be suitable for organic production.

Trellising Isn’t an Effective Control

We also wanted to test how well trellising reduces downy mildew severity. In theory, trellising raises vines off the ground and allows leaves to dry faster, thus reducing downy mildew.

But trellising had minimal effects on downy mildew development and did not increase marketable yields. It’s unlikely that it would be worth the cost or the time to set up trellises.

If producers grew cucumbers as the crop following tomatoes, and trellises were already in place, there may be a slight benefit. But it’s not guaranteed.

We did not measure any appreciable differences in the length of leaf wetness periods between the sunny and shady sides of trellised plots, or between trellised and non-trellised plots.

The Role Costs Play

For each method, we calculated expected net returns. Overall yields had the greatest effect — much more than each control practice’s direct costs.

Seven fungicide applications cost $109 per acre. Trellising cost $404 per acre. Seed cost $96 per acre for ‘Bristol’ and $70 per acre for ‘Speedway.’

The highest net return was $12,690 per acre with fungicide-treated ‘Bristol’ in the spring. This value includes jumbo fruit, because we assumed most of these fruit would have been U.S. No. 1 extra if we had harvested more often than twice per week.

How We Assessed Results

For our study to be useful to growers, we rated those areas that have the greatest impact on production.

Disease Severity. We visually rated downy mildew severity seven times in the spring and six times in the fall. We rated each side of the trellised and non-trellised plots separately to capture any differences between the sunny and shaded sides of the trellised plots.

Grading Cucumbers. We graded fruit into U.S. No. 1 extra, large, and small sizes and weighed them. We applied wholesale prices for the three sizes on each harvest date. Those prices came from USDA, AMS (Agricultural Marketing Service), Specialty Crops Market News for cucumbers produced in South Carolina and sold at the Columbia, SC, terminal market.

Confidence Levels. We analyzed all disease and yield data statistically and compared treatments at a 99% level of confidence that the differences observed would be reproducible.

How We Structured the Study

When and Where: Spring and fall 2017 in Charleston, SC, at the Clemson Coastal Research and Education Center.

Bed Configuration: Individual plots were single rows, 15 feet long, with seven plants per plot.

Mulch: We covered raised beds with black polyethylene mulch in spring, and white-on-black polyethylene in the fall and supplied drip irrigation.

Timing: We seeded cucumbers on May 10 and August 8. We chose the late spring date (for coastal South Carolina) to increase the chance of downy mildew exposure.

Harvesting: The team harvested cucumbers six times each season (twice per week), starting on June 20 and September 21.

Our Three-Tier Design for the Study

Tier 1: Fungicides. First, we divided the fields into fungicide-treated and non-treated plots, replicated three times.

The fungicides used were chlorothalonil (Bravo Weather Stik), 2 pints/acre, alternated weekly with cyazofamid (Ranman), 2.75 fluid ounces per acre.

We sprayed Chlorothalonil four times and cyazofamid three times. We sprayed control plots with water.

Tier 2: Trellising. We divided each fungicide and water plot in two. In one, we made simple stake-and-twine trellises. For the other half, vines grew on the ground as usual.

Tier 3: Cultivars. Finally, we seeded resistant ‘Bristol,’ or a related susceptible cultivar, ‘Speedway,’ in one of the two rows in each trellised or non-trellised plot.