California Crush: Wine Grape Haul Too Big To Sell

The California wine industry is at an inflection point, with too many grapes in the ground finally catching up with the industry in 2023.

The 2023 crush totaled 3,899,710 tons, up 6.2% from the 2022 crush of 3,670,861 tons. While that is not a record, Jeff Bitter, President of Allied Grape Growers, says it is the biggest crush since 2018. The reason it was not a record is because not all the grapes were crushed. Far from it.

“The real issue is what’s not in the crush report — an estimated 400,000 tons that didn’t get harvested,” Bitter says.

The crop would have produced 4.1 million tons, based on the acreage and assuming 90% would find a home, Bitter says. Obviously, a lot of the grapes did not find a home and were left on the vine. The grapes that did not sell were not contracted for, and growing on spec in this environment makes little sense.

However, some growers in the San Joaquin Valley had problems with quality because of the remnants of a summer hurricane. The highly unusual weather created a lot of moisture in a region that is normally bone-dry in August and September. Bakersfield table grape growers likely got hurt the worst, but wine grape growers also ran into problems with mildew, Bitter says.

“Some growers had quality issues, and so many wineries wanted to get out of contracts,” he says. “Lots of ‘Zin’ in the center of the state got rejected for rot.”

REDS TO BLAME

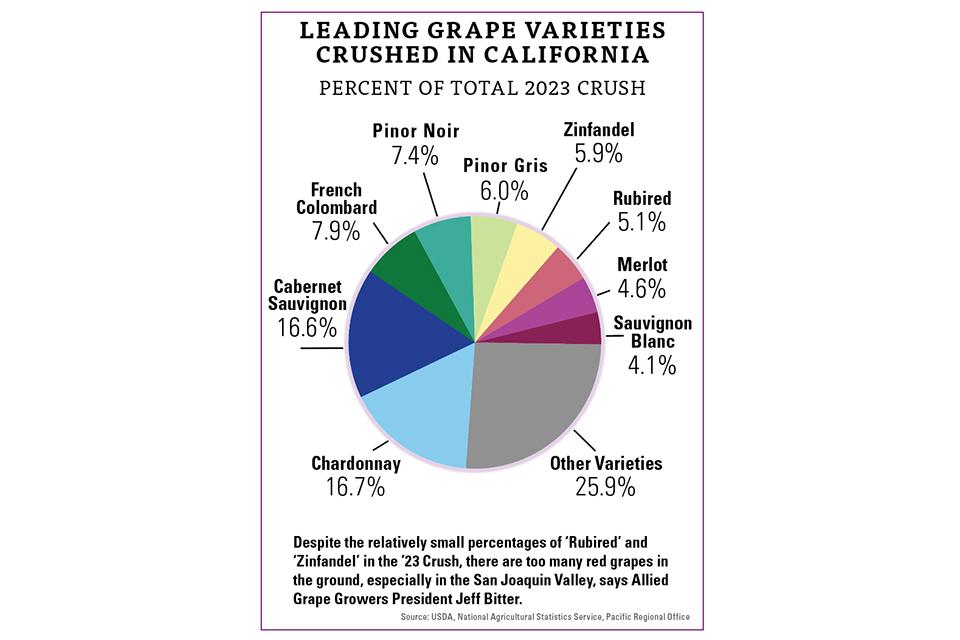

Red wine varieties accounted for the largest share of all grapes crushed, at 1,970,643 tons, up 3.0% from 2022. It definitely would not be that way if it were up to Bitter. Not that growing grapes for white wines looks incredibly bright, but the prospects are much better than for red wine grapes.

“If you look at the center of oversupply last year, it was on the red side,” he says. “It’s not varietal-specific, just color-specific.”

Bitter says he looks at other factors, such as the areas of the valley that got grapes rejected, and could still find just the one common factor. “If you look at the grapes left on the vines last year, it was reds, and that was everywhere,” he says. “Even ‘Zinfandel’ in Lodi.”

Bitter was particularly disappointed because 2023 was the first year since 2020 when all the state’s grapes were not harvested.

Combine that with the fact that wine consumption is down all over the world. That means there is no export market eager to snap up the state’s excess wine grapes. “You can’t sell a guy a steak dinner if he’s full,” Bitter says.

Millennials simply do not consume as much wine as baby boomers, and those in the latter category are dying off as millennials take over. Bitter says the Wine Institute is putting together a campaign to encourage moderate wine consumption, but that is clearly going against the tide. American wine consumption per capita has dipped to its lowest level in two decades.

CHANGE IS COMING

Obviously, not all growers are going to continue farming wine grapes in California, Bitter says.

“Without a doubt, you’re going to see lots of growers get out of industry,” he says. “The smaller guys are struggling to make it. Why beat your head in when you’re 75?”

It is especially difficult for those older growers with no succession plans.

“What will that mean for land use in the area? Most politicians don’t want to see little guys fail,” Bitter says. “We’re going to see if we can provide assistance because ag land abandonment will be an issue.”

Bitter believes wine grapes will not be the only permanent crop to face such an inflection point. It is the first to have such serious problems, but it certainly will not be the last.

“All permanent crops take real investment,” he says, “and none are showing a permanent price.”