Stink Bug Update

From meager beginnings in small gardens in residential neighborhoods to becoming a produce super villain synonymous with devastating losses in fruit crops, the brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) has made its rise to notoriety in less than a decade. Now that this pest has been found in more than half of the U.S., fruit growers are battle veterans. Vegetable growers, however, have been trying to learn from the progress made from the tree fruit growers’ struggles.

Shelby Fleischer, a professor of entomology at Penn State University, says he has already seen significant damage in sweet corn, peppers, and soybean crops in Pennsylvania, and tomatoes eggplants, okra, and other legume crops are also at risk.

Knowledge Is Power

Although researchers are still decoding the behavioral patterns of the stink bug, Fleischer says that studies have shown there are distinctive choices being made when it comes to the bug’s behavior. One behavioral pattern, for example, that vegetable growers can learn from is that stink bugs overwinter in sheltered locations.

“This includes houses, man-made objects, and under tree bark,” he says. Because of this, fruit growers may have had a hard time protecting crops with sprays due to the fact that the stink bug has a tendency to hide.

Fields near forests need to be watched closely, he says. Known as the “edge effect,” the rows closest to wooded areas receive the highest pest pressure because the stink bugs generally come to the crops from their haven in the trees. In order to combat this, growers should target scouting and controls around the perimeters of fields.

Fleischer also says trap crops may be an effective crop protection tool. Although there is still much research to be done in this area, he has received reports that sunflower plantings have distracted the stink bugs from pepper crops. One downside of the flower plantings, however, is that they attract pollinator species, “and we don’t want to kill pollinators,” he adds.

Fleischer makes it clear that growers should remain vigilant. “I would have a routine of at least once a week when you’re checking your field,” he explains. “I would scout right when plants start setting fruit.”

A Good Defense

Damage inflicted by the bug varies. “Adults and mobile nymphs seek out live tissue that is rapidly reproducing,” he explains. This, in itself, is the reason why the stink bug has been so detrimental to the produce industry; they go for the buds and maturing fruit, rendering the crop unmarketable.

“You can tolerate a lot more foliar damage than damage to the produce itself,” he says. In addition, Fleischer says that insect damage is out of proportion to its density. “They probe and feed, and then move, and probe and feed again, causing widespread damage.”

In order to find out what chemical controls should be used, Fleischer suggests using commercial vegetable production guides for tailored information. In addition, growers should develop a relationship with their local Extension representatives for up-to-date information.

For more information on the difference between beneficial stink bugs and herbaceous ones, please turn to page two.

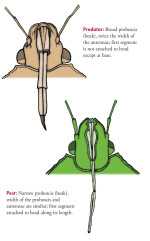

Shelby Fleischer, professor of entomology at Penn State University, emphasizes the importance of knowing the difference between beneficial stink bugs and herbaceous ones, or ones that consume specialty crops. Beneficial stink bugs feed on many species of plant-eating insects, reducing the number of pests in the field, he explains.

Encouraging growers to use a magnifying glass to get to the bottom of their stink bug concerns, Fleischer explains that beneficial insects have shorter, thicker mouth pieces that are not used for piercing buds or fruit but for attacking damaging pests.

Herbaceous stink bugs, or ones that feed on buds and fruit damaging the quality of the crop, have long, thin snouts. The famed brown marmorated stink bug can also be identified by the white stripes on its antennae.