Why Pome Fruit Growers Need To Prepare For More Unusual Weather

With the apple industry facing tough times, organizers of the 67th annual meeting of the International Fruit Tree Association (IFTA) in Yakima, WA, titled the conference: “Bridging the Gap Between Information and Action.” As talk among growers these days frequently centers on unusual weather events, presumably caused by climate change, IFTA Research Director Greg Lang led off the conference with sessions on climate adaptation.

Climate change is quite real, Denise Neilsen of Pacific Agri-Foods, British Columbia, said. It weakens the jet stream, allowing for greater temperature swings, she said. It has also been known to cause the infamous “Polar Vortex,” which lets the cold Arctic air swoop down, affecting new areas. Thus “global warming” can cause cold weather problems, even though Neilsen noted the winter minimum temperature over the past century has risen 2° C.

“All extreme weather events are attributable to climate change,” she said. “They often go with drought and flooding.”

Cold weather events, which are most damaging to growers, have increased in recent years. There were none in the Pacific Northwest between 1990 and 2022, but then serious problems occurred back-to-back in 2023-2024. Particularly troubling in the future are weather models showing there are likely serious droughts in the cards. Neilsen predicted that, between 2040 and 2100, growers will be short of water 50% of the time.

CUT IRRIGATION IN HALF

David Eissenstat, Penn State University Emeritus Professor, who Lang described as “a world-renowned root biologist,” agreed growers should prepare for having less water in the future in case they lose access. They may well be quite surprised at what they learn.

“Roots have the potential to tap deeper in dry years — trees have resilience,” he said. “Though they must be exposed repeatedly in dry years, or the roots won’t go deep.”

By easing them in this way, Eissenstat said the trees can essentially be trained to live, even thrive, on much less water than most growers think. He then followed up with an eye-popping statement: “Restricting water to 50% ET (evapotranspiration) will not affect the yield if the trees are conditioned to it.”

Tianna Dupont, Washington State University, said increasing temperatures, which the Pacific Northwest has weathered in the past few years, increase the spread of fire blight. Dupont said she was part of a large multi-pronged effort led by Michigan State University researchers George Sundin and Nikki Rothwell that focused on putting together different fire blight products into programs, as no products are sufficient as a stand-alone.

Apple cold hardiness, tree decline, and climate change (ifruittree.org)

Source: Jason Londo, Cornell University

ROOTSTOCKS GET COLD?

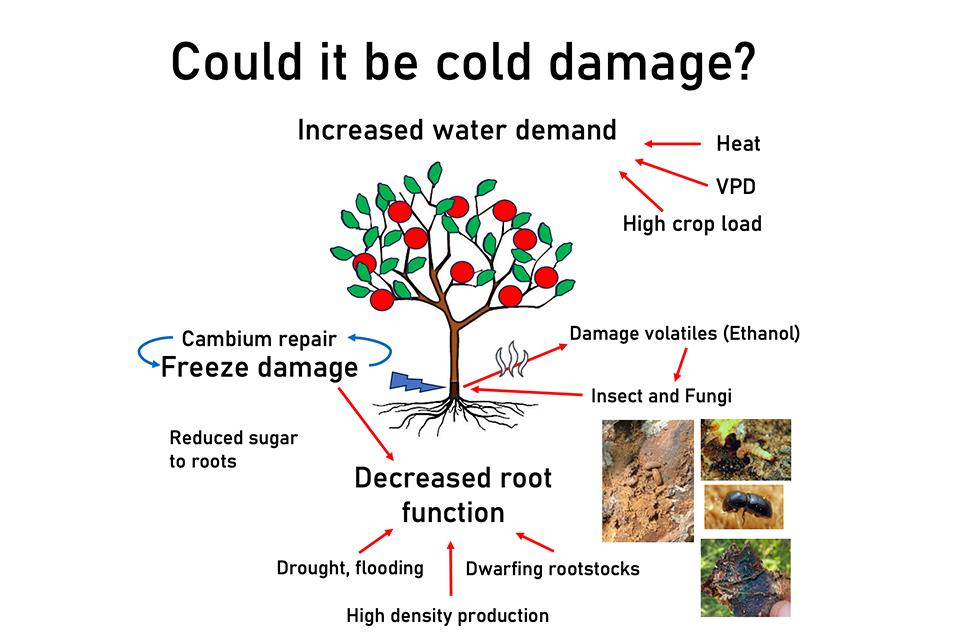

However, most fruit growers sustain losses because of cold events. Jason Londo of Cornell University has been examining a little-studied topic — the cold hardiness of apple rootstocks. In a “cold” year, he said cold hardiness is variable, but in general all the rootstocks he tested are sufficient to avoid typical damage. In a “mild” year, some rootstocks demonstrate reduced acclimation response, and others demonstrated limited de-acclimation resistance by mid-winter and are at increased risk of cold damage. M.9 and G.11 are potentially problematic, Londo said.

“Snow cover works as a blanket.” he added. “In a mild year is when it gets nasty,”

Londo also looked at whether grafted trees experience winters differently, and whether this could explain tree decline symptoms. In a cold winter year, such as 2021-2022, scions and rootstocks were in close synchrony for cold hardiness, with rootstocks typically a little more cold hardy.

In a mild winter year, such as 2022-2023, scions and rootstocks become desynchronized, with some rootstocks becoming less cold hardy than such common varieties as ‘Gala’ or ‘Honeycrisp’, and there being more evidence of late winter de-acclimation sensitivity. This past winter, 2023-2024, was definitely a strange one, as Londo said half of the rootstocks he is testing “see” the winter as cold, half see it as warm.

Cold hardiness traits are one of many traits to consider in rootstock choice, Londo said. Whether the importance of that trait relative to others rises or falls in the future is yet to be known. Not only that, but no one also knows what may be in store in this crazy climate.

“All winters are weird, and they’re getting weirder,” he said. “There are no normal years anymore.”