Optimizing Soil pH for Organic Blueberries From the Ground up

Soil preparation and conditioning are key when working with organic crops. Here, surface-applied sulfur is used during bed prep.

Photo by Scott Lukas

Blueberries are a big deal in the Pacific Northwest (PNW), especially those destined for the high-value organic market. Approximately 60% of the nation’s total organic blueberry volume is sourced from Oregon and Washington. That number is anticipated to rise as more blueberry is planted and recently planted fields mature.

Despite the scale and significance of the PNW organic blueberry industry, growing this high-value crop is not easy. This is especially the case for growers located east of the Cascade Range, where most of the organic blueberry acreage is concentrated. While soils east of this area support a diversity of high-value crops, they are in some ways opposite of what blueberry requires.

“Low rainfall in the semi-arid region east of the Cascades has slowed the natural soil acidification process, resulting in calcareous soils with pH values far too high for an acidophilic plant like blueberry,” explains Dr. Scott Lukas, Assistant Professor of Horticulture at Oregon State University’s Hermiston Agricultural Research and Extension Center.

Blueberry requires acidic soil conditions ranging from pH 4.2 to 5.5 to thrive. Yet native soil pH levels east of the Cascade Range where organic blueberry is concentrated typically have a soil pH at 7.0 or above. Growers, in turn, must carefully modify the pH of their soils using acidifying agents, which takes time and money. In some cases, more than a year.

Alex Gregory, a graduate student in Lukas’ program, provides further details. “Currently, growers will surface-apply elemental sulfur in the form of prills and then allow up to a 12-month fallow period before planting to give the prills a chance to break down and begin reducing soil pH before incorporating it into soil directly before planting. But even with this management technique, growers in our region still need to acidify irrigation water using expensive and hazardous sulfur burners nearly every time they irrigate to ensure the soil solution surrounding the blueberry roots is within the ideal pH.”

Lukas is keenly aware of these challenges and has set out to provide recommendations based on research that he and Gregory are leading through a USDA Organic Transitions Program grant.

“The goal of our project is to improve nutrient management in organically produced blueberry by developing streamlined methods to expedite the soil acidification process,” Lukas says.

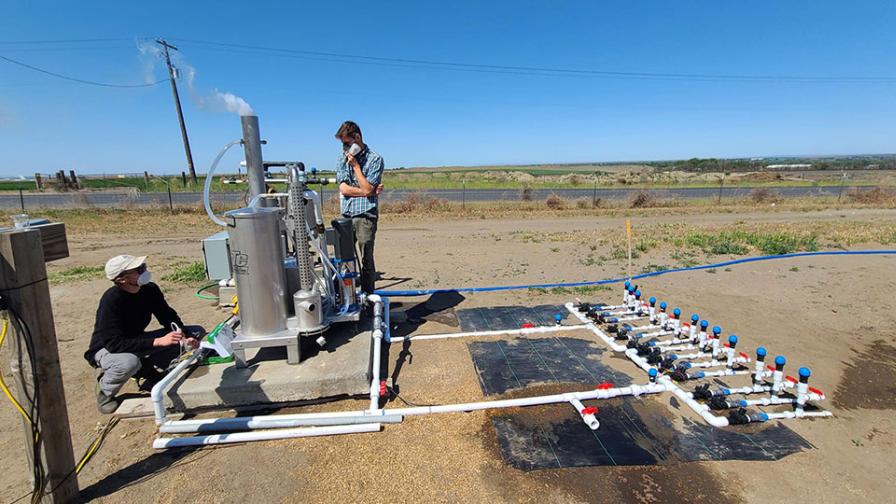

Alex Gregory (right) operates a sulfur burner with L. Clark.

Photo by Alex Gregory

EMERGING TRENDS

In a multi-year experiment located in Hermiston, OR, Lukas and Gregory are comparing different rates, formulations, and application timings of elemental sulfur to standard industry practices to find ways growers can improve soil pH management that lessens fallow periods and the dependency on complicated sulfur burners.

While the experiment is ongoing, some trends have emerged. “Treatments have experienced a rapid decrease in pH over the first six months after application,” Gregory says, “which slows before pH begins a gradual creep upwards. Even in plots receiving acidified irrigation water, this upward [pH] creep is still present.”

Increasing pH after soil acidification is an experience shared by growers. However, treatments that have received dry prills directly before planting experienced a lower drop in pH, and the gradual rise in pH has been slower than industry controls that included an 8-month fallow period prior to prill incorporation and planting.

“This suggests growers may be able to adequately manage soil pH while being able to bring their new plantings into production up to one year sooner,” Gregory says. But caution is warranted, and the researchers encourage growers to wait until the study is completed before changing practices.

The research team is also using unmanned aerial systems (UAS)-based sensors with an aim to develop approaches to rapidly assess plant growth and health. Gregory is excited about these tools for his research but also sees practical value.

“The barriers to entry in terms of both cost and technical ability for using UAS-based sensors is decreasing all the time.” While UAS are being increasingly used and promoted, Gregory is leading an assessment of product accuracy and feasibility so growers and researchers alike can gauge the utility of these new technologies.

While the research is ongoing, future results will contribute to the limited but growing number of studies that will provide data-driven recommendations to enhance organic blueberry production in this economically important region.