Soil Samples Allow Scientists To Dig Deeper Into HLB

Photo by Frank Giles

While the work of mitigating the effects of HLB in recent years has largely focused on what is happening above the ground with foliar nutrition applications and psyllid control, there is growing acceptance that what is happening below the ground is equally important. It is understood that root health is affected by HLB and should be managed in conjunction with all other HLB efforts.

Since the late 1980s, Syngenta has been collecting soil samples at the request of growers who were interested in keeping track of phytophthora occurring in their groves. The soilborne organism causes fibrous root rot and foot rot in susceptible rootstocks. The free sampling program was started in support of the company’s fungicide product Ridomil Gold (mefenoxam), which is an important tool in phytophthora management in rotation with other products.

The sampling program has been largely run by college interns, some of which have joined company as full-time employees after their internship. According to John Taylor, agronomic service representative with Syngenta, for many years, the number of samples requested by growers and the percentage of samples that were at treatment thresholds for phytophthora remained fairly stable. But, that began to change in 2010, as growers began to see more and more decline of trees in their groves.

“There was beginning to be dialogue among growers about the possible interaction between HLB and phytophthora starting in late 2009 and then more so in 2010,” says Taylor. “That is when we began to see a huge spike in requests from growers for soil sampling.”

There was a realization that HLB was interacting with phytophthora. While one malady does not cause the other, the two ailments were interacting. The hunch of a connection was confirmed

in spring 2011 when Dr. Jim Graham, UF/IFAS, learned of a study from Taiwan that drew a correlation between HLB and phytophthora. In essence, the study suggested HLB in trees predisposed roots to greater attraction of the zoospores that cause phytophthora and leaves roots less resistant to invasion by the pathogen.

“That opened the door to a broader question of what is HLB doing to the roots of citrus trees,” says Taylor. “Even in the absence of phytophthora or any other pathogen, you already are seeing a 30% to 40% loss in roots just due to HLB. You start throwing in soil pathogens, nematodes, insects, and poor water quality, it is enhancing the negative effects on the root systems.”

“We have been using the Syngenta sampling program for phytopthora for at least 20 years,” says Scott Lambeth, production manager for Golden River Fruit Co. “The benefit is that it gives the grower a base level we are treating yearly. We have been on a Ridomil program off and on for more than 30 years.

“With the introduction of HLB, root health is more important than it has ever been. Controlling phytopthora is just one component of maintaining tree health in the face of HLB. We are now lowering the pH of our irrigation water to help with the high bicarbonate levels that are prevalent in our waters. Root health is a daily concern and I am looking into every aspect of our production program to keep our mature root systems viable. Keeping our mature groves at their highest level of production is a priority.”

Threshold Hits Ramp-Up

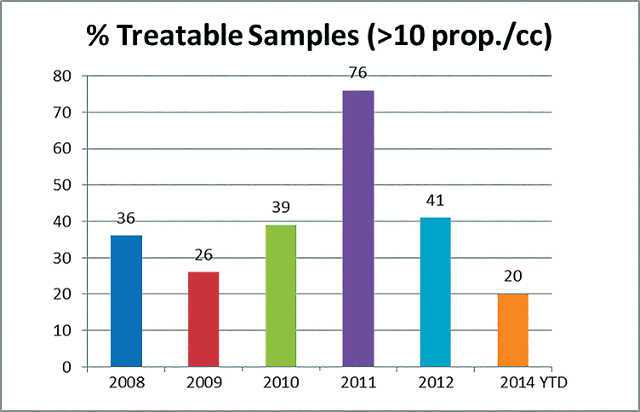

The historical data being collected by Syngenta also suggests something new is happening to the roots in the presence of HLB. Historically, the percentage of samples pulled that were at or exceeded the UF/IFAS treatment threshold for phytophthora (10 propagules per cubic centimeter) had vacillated roughly between 25% to 35%.

“In 2010, we saw this number begin to move,” says Taylor. “Then in 2011, the numbers jumped to 76% of samples that were at threshold for phytophthora treatment. One hypothesis is HLB really began to ramp up in trees and spread across citrus groves in 2011, which brought the spike in phytophthora levels.”

In 2012, the percentage of threshold samples declined to 41%. Taylor notes one way of interpreting the drop in phytophthora thresholds might be because there is less root mass to attack due to advancing HLB. “We saw this number go down on the same year we saw the big fruit drop,” says Taylor. “The data might be a leading indicator of the progress of HLB in our groves.”

The chart illustrates the spike in threshold treatment levels for phytophthora in 2011, followed by a drop in 2012.

Source: Syngenta

At posting, threshold levels for phytophthora in 2013-2014 were trending lower than the historical range at 20% during a year where conditions were ripe for phytophthora statewide. Taylor says there could be several factors influencing this, including advancing HLB’s destruction of roots and the fact there has been a dramatic increase in fungicide treatments to protect roots in the past two to three years.

“Watching these trends in the data leaves us scratching our heads,” he says. “Unfortunately, right now, decisions are being made on hypothesis, because we just don’t have time to develop bottom-line recommendations and refine the data the way we normally would.

“HLB confounds these types of observations as well, because it is not a static disease. Trees are continuing to get infected and there are varying degrees of infection in trees. When you go out into a grove system and disease symptoms are so variable, it is very difficult to tease out what is going on.”

Changing Flush Patterns

Another pattern Taylor is observing in the groves and in phytophthora root data is that HLB-infected trees’ ability to produce foliage and root flushes is being impacted. And, it may be shifting the window of need for phytophthora soil sampling, which has traditionally occurred from mid-May to mid-August. “Historically, this is when we’ve pulled samples, because this was the window of phytophthora activity,” he says. “But, we are getting more and more requests from growers for samples to be pulled outside this window. I think this is an indication of changes in the trees.

“This summer, we saw phytophthora numbers trending down throughout the summer, which left us confused because it was raining like the dickens and conditions were perfect for it statewide. My operating theory is we are now seeing a lot of growth before and after bloom, but we are not getting much foliage flush during summer like in the past, and thus, not much of root flush either.”

With 30% of a tree’s root system lost to HLB alone, it is less able to source nutrients and store carbohydrates to fuel flushes and support a full crop load. “Maybe now we are going to start seeing only one or two significant growth cycles in these trees per year,” says Taylor. “In 2013, we saw modest disease activity from January through March, which would correlate with our spring flush period. Then, disease levels declined throughout the summer. Field observations seemed to indicate the majority of trees were producing minimal new growth during this period. At the very end of August, trees statewide began to show significant new growth and at the same time we have seen a sharp and sustained increase in phytophthora levels through November. It leads me to wonder if we need to be pulling samples a little earlier and later around the summer months. I am reluctant to cease summer sampling because we need those data points, too. My goal in 2014 is to pull more samples in those historically slower periods.”

Ridomil Gold applications should be timed to coincide with periods of root growth and disease activity. Historically, that has meant a late spring/early summer application followed by another application in late summer to early fall. With HLB possibly impacting the timing and number of root flushes, growers may need to adjust the timing of their phytophthora controls in coming seasons.

While researchers still learn more about what is happening between HLB and the root system, Taylor says his company’s data only reinforces the growing consensus that HLB-infected trees can ill afford any form of stress above or below the ground. “We have got to manage all these stresses on trees whether it is phytophthora, high bicarbonates in irrigation water, and anything else that can cause problems. It’s a real challenge to identify key stressors and develop mitigation strategies that can be quickly and economically implemented. As has been the case in past challenges, the breakthroughs seem to come when growers, researchers, and industry share their observations.”