Repelling Aphids

As many pepper growers know, cucumber mosaic virus represents a thorny problem. In University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor Joe Nunez’s part of the country — the south end of the San Joaquin Valley — the virus has proved tough to pin down since it first appeared about five years ago. “There is no pattern as to when it appears or how severe the infection will be,” he says. “Some fields have had minor infections, and some fields have had more than 50% yield reductions, but we’ve also had fields that they didn’t even bother harvesting, let’s put it that way.”

As many pepper growers know, cucumber mosaic virus represents a thorny problem. In University of California Cooperative Extension Farm Advisor Joe Nunez’s part of the country — the south end of the San Joaquin Valley — the virus has proved tough to pin down since it first appeared about five years ago. “There is no pattern as to when it appears or how severe the infection will be,” he says. “Some fields have had minor infections, and some fields have had more than 50% yield reductions, but we’ve also had fields that they didn’t even bother harvesting, let’s put it that way.”

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) also doesn’t affect all peppers the same way. While it can be quite serious on the long bell peppers, it doesn’t seem to be much of a problem at all on other bells and chili peppers. Because of the way it only hits certain types, many growers felt CMV might be coming in on transplants. But after checking hundreds of transplants, which all proved clean, Nunez became convinced that CMV was being vectored in the field by aphids. It can be vectored by several species of aphids, but most efficiently by the cotton aphid, Aphis gossyppi, and the green peach aphid, Myzus persicae.

What’s particularly problematic is that killing the aphids doesn’t necessarily prevent CMV. Even though the plants are treated with a systemic insecticide from the time they are young seedlings, fields are still being infected. That’s because once an aphid lands on a plant it immediately begins to probe to see if the plant is a suitable host, says Nunez. Once the probing begins, the virus is transmitted. The insecticide may do in the aphid, but not quickly enough.

“Killing them doesn’t do any good,” he says. “You’ve got to keep them from landing on the plants in the first place. That’s where I got the idea to repel them.”

How To Repel?

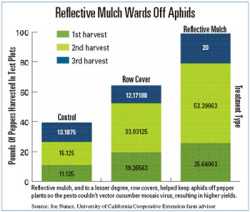

Nunez then set up a trial this past spring that included three basic methods: insect repellents, reflective mulch, and insect barriers. The insect repellents were composed of a variety of commercially available botanical oils such as citronella and garlic oil. From experience, he didn’t think they would work too well, but growers had requested they be included, so he agreed. However, they didn’t perform any differently than the control.

For an insect barrier, he tested material similar to that used in a hair net — the lightest weight available with a weave tight enough to prevent aphids from getting through. For a reflective mulch, he tested a silver type. Both the row cover and the reflective mulch performed extremely well in keeping aphids off the plant and preventing CMV. About the only difference was that the row cover did have reduced yields in a couple plots. Nunez suspects that the row cover shaded the plants too much, thus preventing the plants from reaching their potential.

One final factor for growers to consider is that some already use mulches to reduce weeds, etc., so they may want to consider a reflective mulch. Those growers who choose not to use mulch should stay tuned, however, because this coming year Nunez will be testing what he believes may well be a viable low-cost alternative. (See “Painting Soil.”)