Citrus Industry Stakeholders Look To Stay Positive Amid Challenges

At this point in the game, many U.S. citrus growers, particularly in the Southeast, appear to be lining up for Hail Marys in their ongoing battle against the Asian citrus psyllid (ACP) and the incurable disease that the pest vectors, Huanglongbing (HLB).

When asked about the future of their industry, considering the devastating disease, a one-word answer frequently appears in American Fruit Grower’s annual State of the Industry survey results from Florida growers who have been battling it for more than a decade:

“Bleak.”

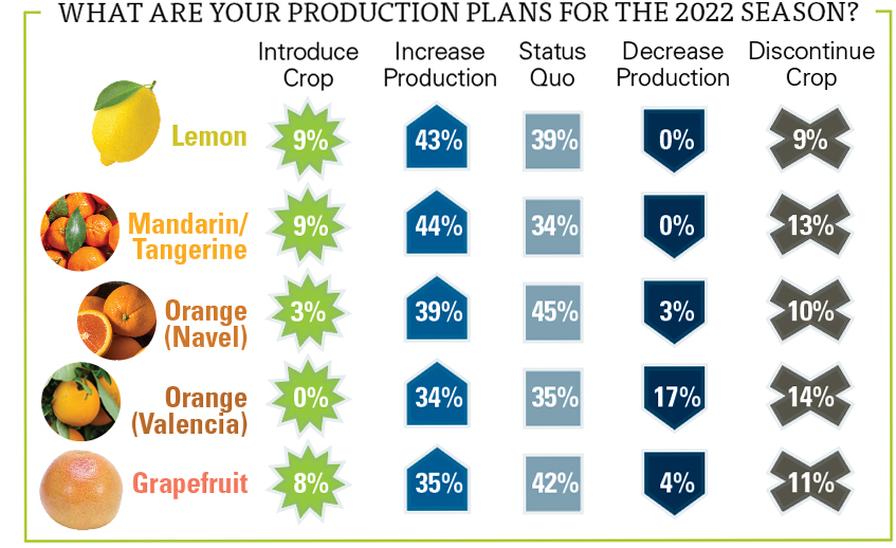

Production plans for 2022 illustrate the issue. Between 9% and 14% of the growers of the five most prominent citrus fruits — orange (navel and Valencia), lemon, grapefruit, and mandarin/tangerine — indicate they are discontinuing their crops this season. Among the 22 fruit types tracked in the survey, the only other one in a similar situation is apricot at 10%.

“Unless there is a radical breakthrough in the next couple of years, the citrus industry in Florida is doomed,” a grower from the state says. “Greening has decimated the citrus industry.”

That sentiment is shared across the Sunshine State. “Survival as an industry competing in a global market is doubtful,” a Florida grower says.

“Research has failed us,” a counterpart laments. “Greening disease is killing us!”

“I’m diversifying until there is a real cure,” another Florida grower says.

WEST COAST VIEWPOINT

California growers, who have so far avoided the brunt of the incurable disease, are waiting for the other shoe to drop.

“I feel like we are always at risk for the infestation,” a grower says.

In turn, they have taken the defense and are adamant about doing so. One grower — replying in ALL CAPS — insists that his peers be vigilant and treat when an infestation is near or in their groves.

“Hopefully, we can all work together and keep up with spraying to keep numbers down,” another California grower says.

Spraying, however, can be costly in many ways.

“We harvest three times a year. We are mandated to spray before every harvest,” a California grower says. “The cost of spray and harvest has cost us financially, and biologically it’s malpractice to kill good bugs.”

“We’re hoping for an organic solution,” a California counterpart says. “We haven’t seen it yet at our farm.”

Some California growers say they have real trepidation about ACP/HLB, but most others say it is not a huge problem yet, and they see the future as bright.

Regardless, “we need to keep up the research,” another grower echoes. “We need a cure.”

ELSEWHERE IN AMERICA

Growers from states other than California and Florida offer noteworthy comments. While one grower feels “fortunate” to be in Arizona, a counterpart in the state notes that old trees do have a hard time resisting HLB infection.

“There is a need for resistant plants,” a grower from Texas adds.

From another Texan, “We have not seen any adverse impact from ACP. It’s very easy to control with a regular spray program.”

Finally, life is swell in, where else, Hawaii. “My production is good,” a grower checks in from the island of Maui.

PROBLEMS AND SOLUTIONS

Other complications that affected the citrus industry in 2021 included the water shortage in California (“there’s not enough water to size the fruit, so we had small fruit”), significant hurricane damage in Texas, and fruit drop in Florida.

“We grew a good crop, although a little light,” a Florida grower says. “However, the trees would not hold the crop, especially in the Valencias. Drop was larger than ever.”

Climate change is cited by one grower in California.

“Production does not seem to be consistent,” he says. “Ripening and harvesting of fruit has drastically changed over the past five years. The weather — climate change — is real and affects the fruit.”

Unwelcome news notwithstanding, profits were made in 2021. Reasons why include cutting labor, minimizing tillage, delaying expenditures, and increasing new plantings. Temporarily reducing expenditures for fertilizer worked in some cases; in others, applying more foliar nutrients did the trick.

“We fertilized more often, but with less quantity, and the year-end application was the same,” a Florida grower says.

“I improved production in all the oranges dramatically by more appropriate pesticide and fertilizer management,” a California grower says.

Finally, another grower in the Sunshine State recommends constantly communicating with the packinghouse: “Please, pick our fruit and not delay it.”