Can Do — Why Processed Peaches Are Making a Comeback

Over the past few decades, almond prices soared and peach prices — especially for peaches intended for processing — stayed fairly stagnant in comparison. The crops are quite similar to farm, and seeing the relative prices and the fact the nuts could be grown with a lot fewer workers, a lot of California peach growers switched much of their land over to almonds.

But over the past few years, it’s not the peach prices that have been in the pits. Almond growers have grown dismayed at dropping prices, leading them to look for new crops to farm.

“Some of them apparently still remember how to grow peaches,” says Eric Spycher, chuckling. “Seriously though, a lot of those farmers are like us, they have nuts and peaches. They have just shifted over some of their acreage.”

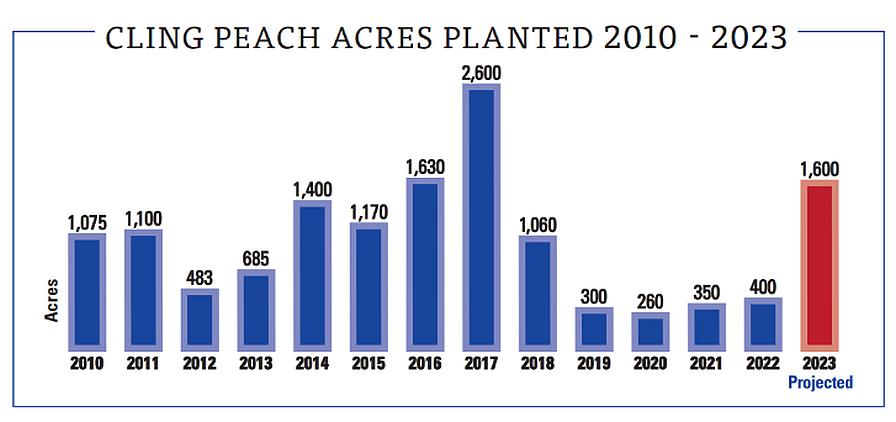

Graphic courtesy of California Canning Peach Association

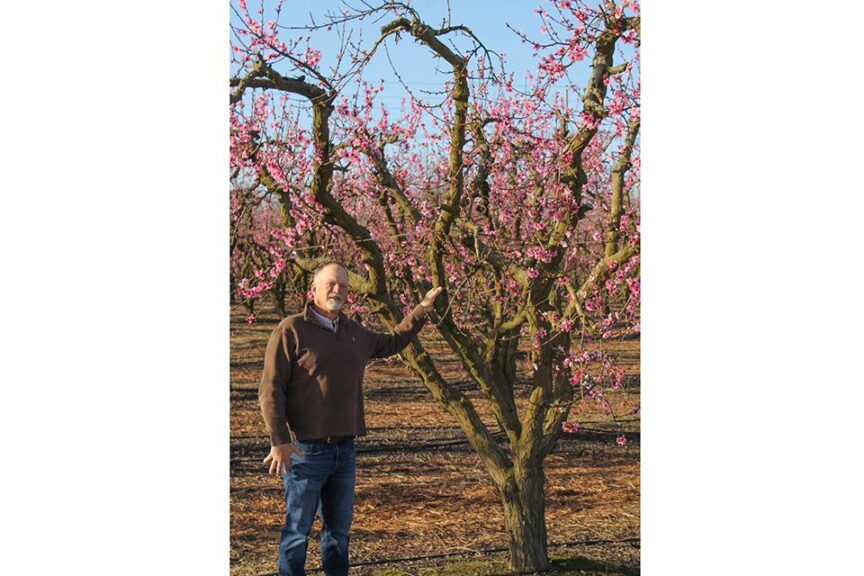

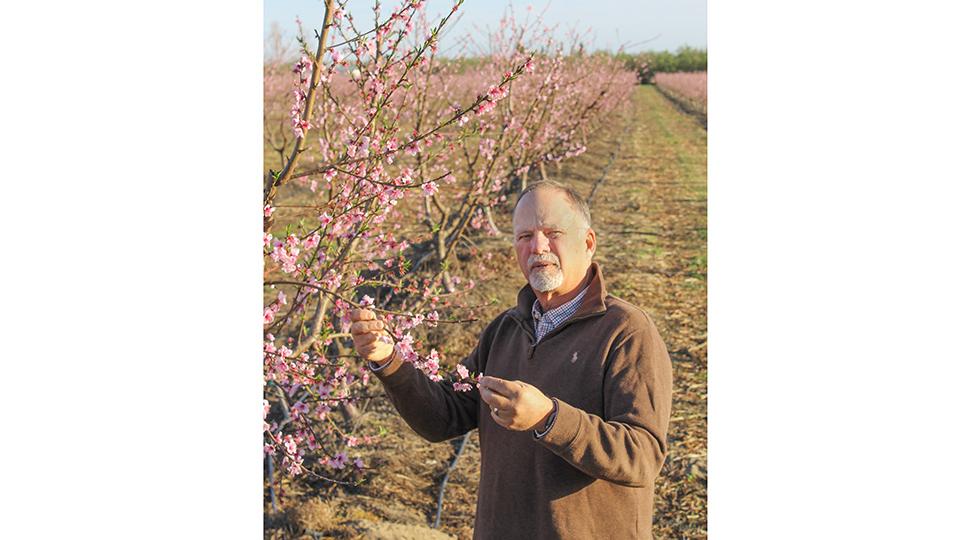

Spycher grows peaches and almonds — “with a dab of walnuts” — with his dad Hartley and brother Kurt at Spycher Farms Inc. in Ballico, CA. He’s a third-generation peach grower, though economic realities in recent decades have meant they’ve placed about 75% of their acreage in almonds. Spycher also serves as Vice Chair of the California Canning Peach Association, giving him some perspective on the situation in a state that produces the lion’s share on the nation’s processing peaches.

Incidentally, not all processed peaches are cling types. The notion derived from the fact cling varieties hold their shape when canned, making them the superior choice. In more modern times, processors have sought peaches for cutting up and freezing, and freestone varieties — traditionally thought for fresh eating — are preferred for freezing. So while Spycher grows a lot of freestone peaches, he says simply, “I’ve never grown fresh.”

COVID DRIVES SALES

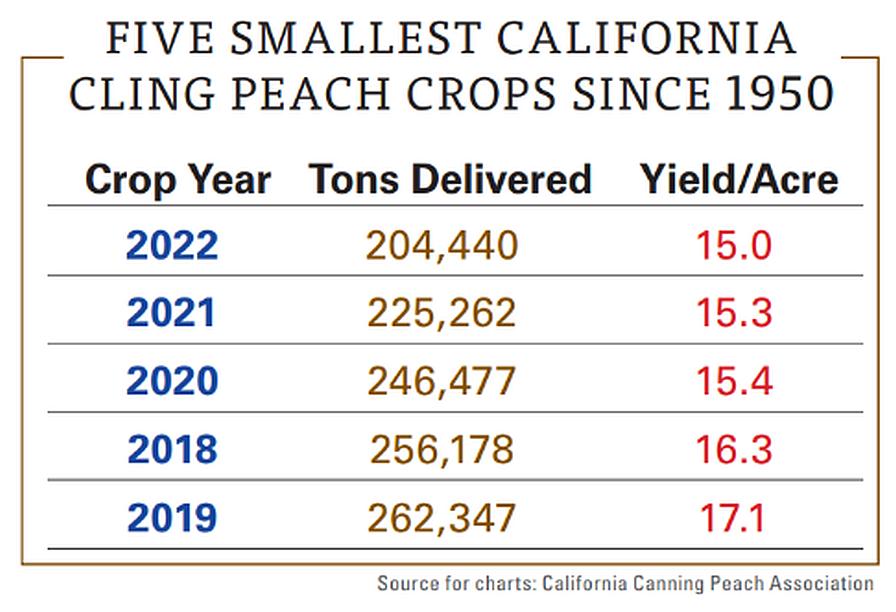

Part of the reason demand for processed peaches has increased in recent times can be attributed to COVID-19, Spycher says. Sales of all canned fruit increased during the pandemic, and peach sales have remained strong since its inception. Before then, prices were flat for quite a while, making them rather unattractive to grow. In fact, the five smallest California cling peach crops since 1950 have occurred in the past five years.

Spycher says those numbers were attributable in part to the state’s drought, which ended with this past winter’s record rains. Another factor is the advanced age and declining productivity of the industry’s trees.

“With the age of the trees, particularly in the Modesto area, there’s been little to no replanting because growers were nervous about [the] industry,” he explains.

However, this year, likely because of the poor almond prices, there’s a lot more planting going on. Projections call for nearly 2,000 acres of cling peaches to be planted in 2023, more than in the entire 2019-2022 four-year period.

Spycher wishes he were as bullish about the long term. The large amount of labor involved in growing peaches — about 70% of his costs — makes margins pretty thin.

For instance, Spycher’s crews pick peaches from about July 10 to Sept. 21 each year and harvest almonds from about Aug. 10 through Oct. 10, making for an eventful late summer.

“In the middle there, when they overlap,” he says with a grin, “it gets a little stressful.”

LABOR PAINS

While the almonds can be machine-harvested, the peaches still have to be harvested by hand. Though it hasn’t been for lack of trying, Spycher says.

“It’s all about bruising. When you hand-pick a peach, it’s cradled,” he says. “If it’s bruised, it’s tough for it to hold up in can.”

Designing a machine that can mimic the human hand has long bedeviled inventors. Because of that, growers have experimented with vacuum systems like those tried on apples, but the fuzz on peaches caused problems with such machines, Spycher says.

Line thinners, like the Darwin thinner, work fine, but they don’t solve any issues with the more difficult tasks, such as harvesting. Spycher says he prefers line thinners to drum thinners, however. The fiberglass arms of the drum thinners were just too rough, he says, leaving damaged and scarred fruit behind.

As for harvesting, he has tried picking platforms like those used with apples. The problem is the trees have to be grown in more of a fruiting wall, and most peach trees are in vase plantings. Spycher says they do have a future, perhaps as a bridge to mechanized harvesting.

In addition, the costs of a fruiting wall system can seem prohibitive. The number of trees is more than double the number found in an acre of traditional vase planting, and with the narrower rows, the water system must be enlarged.

“And the training system? It’s intense,” he says. “I mean, we pruned them all the time.”

BUY AMERICAN

One particular challenge growers of processing fruit face that is not a factor for fresh market growers is they need a contract with a processor. It’s a scenario faced by suppliers of all sorts of products these days, as contraction in that sector of the industry has wide ramifications.

There are just two large processors of canning fruit in California, Pacific Coast Producers and Del Monte. Likewise, there are only two processors of frozen peaches, Wawona Frozen Foods and Dole.

“We have fewer opportunities for marketing,” Spycher says, lamenting the old days when a grower would pick a favored processor — and stick with them. “It used to be you were a one-contract guy, like ‘I’m a Del Monte grower,’” he says. “Now it’s wherever you can get a contract.”

The industry has also been flustered in its efforts to get some major buyers to source their peaches. The California Canning Peach Association’s longtime President and CEO, Rich Hudgins, has fired off letters to major grocery chains asking them to buy American peaches instead of foreign fruit, such as from China. Such foreign competitors often get huge subsidies from their governments, which enable them to undercut American competitors. Of course, U.S. fruit growers, unlike their fellow American growers of program crops such as soybeans and wheat, receive no such subsidies.

More recently, the industry has launched a “Buy American” program that’s aimed at buyers for school districts.

“The idea is we use tax dollars for our own product,” Spycher says. “The problem is tied to price, (school districts) buying from American distributors who source from foreign countries such as China. It’s muddy water.”