That’s Nuts! A Billion Pounds of Pistachios?

In 1968, Ken Puryear, a dentist in a little town north of Sacramento with a keen interest in horticulture, got an offer he couldn’t refuse.

Puryear and the man who would later become his lifelong partner in the nursery business, Corky Anderson were growing 30,000 pistachio plants in a hothouse on Puryear’s property. There were only 400 acres planted in the entire state at the time, and the two men were definitely beginners.

“I had never even tasted one before we planted them — 25 cents for a little bag of ugly red things? No way,” he says, chuckling at the memory of the nuts imported from Iran, which were stained to hide imperfections.

That afternoon, two men came by Puryear’s house: Bill Camp Jr., who hailed from a large San Joaquin Valley farming family, and Milo Hall of Superior Oil, which later spun off Superior Nut Company. Camp and Hall said they wanted to buy all 30,000 trees — for $5 a tree.

“Corky and I were taking a night real estate course at the time. I was late because I was talking to these guys, so I went to the class, tapped Corky on the shoulder and told him,” Puryear says. “That was the end of the real estate class.”

It was a huge amount of money back then, $150,000. So they went back for more seed and planted enough to grow 100,000 plants, and they sold them all for $500,000.

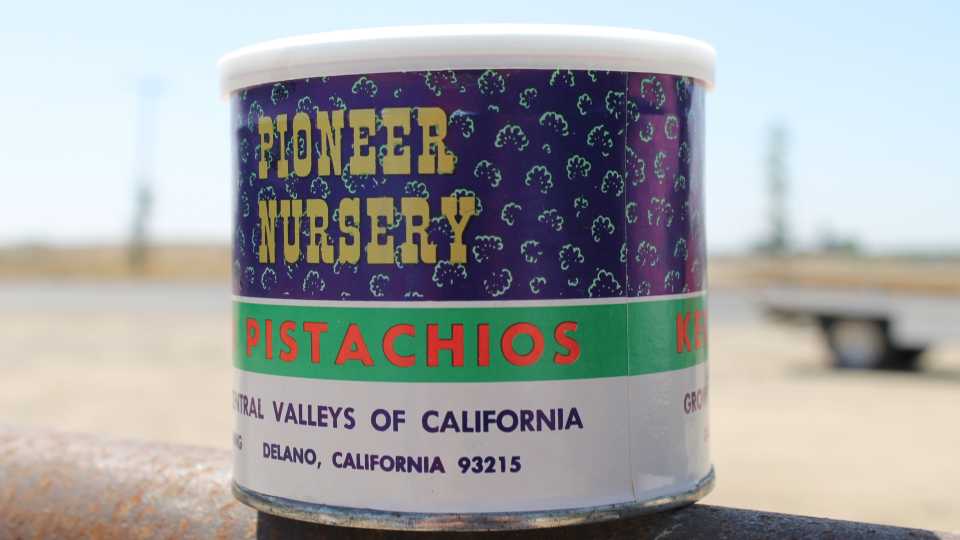

“I was making just $18,000 to $19,000 a year as a dentist,” says Puryear, who then recalls telling Anderson: “This sounds pretty sweet! Hell, let’s plant more, man.” And Pioneer Nursery was born.

Other people soon took notice of all the plantings that originated with Camp and Hall. “That, and the fact that all the trees weren’t dying of verticillium wilt,” says Puryear.

The commonly used rootstocks at the time were Pistachia atlantica and Pistachia terebinthus, and both varieties were prone to the deadly disease. Pioneer Nursery used Pistachia integerrima, which was resistant to verticillium wilt. They later dubbed it Pioneer Gold.

To demonstrate further, in a 160-acre new block north of Bakersfield, they planted five acres of Pioneer Gold in the middle, showing starkly how the trees vastly outperformed the other rootstocks.

“We had to show people, and us, because we didn’t know anything,” he says. “But after that everyone wanted it, and for 10 to 15 years we dominated pistachio nursery sales in the state, because that’s what everyone wanted.”

The industry took off, and today there are 400,000 acres planted in the U.S. It won’t be long before U.S.-bearing pistachio acreage — 305,000, with 99% in California along with Arizona and New Mexico — surpasses that of apples, which are grown commercially in 32 states.

This year the pistachio industry will hit a milestone — the first 1 billion-pound crop. Actually, according to Bob Klein, Manager of the California Pistachio Research Board, the industry will blow by that mark and will likely see a 2020 total of close to 1.2 billion pounds.

FROM COTTON TO PISTACHIOS

Cotton dominated the southern San Joaquin Valley in the late 1960s. One of those young cotton farmers was Carl Fanucchi, who was impressed by the two young nurserymen from Northern California.

“I never saw a partnership like theirs. If one guy said something, the other guy would back it 100%, even if he didn’t agree with it,” he says. “They took a cotton farmer and made me into a pistachio grower, and that’s the best thing that ever happened to me.”

At first Fanucchi was flummoxed by the emerging crop. “Trying to grow this crazy tree? It was nothing like almonds, peaches — any of the trees that have been grown here in the Valley,” he says.

Most fruit and nut trees are budded in the nursery and trained in field. Pistachios don’t lend themselves to that, although Fanucchi says that is changing. They’re planted as seedlings and then budded in the field. Almonds will produce a good crop in third or fourth leaf. Pistachios, even with all the recent improvements, typically take until the fifth leaf, though it used to be the seventh leaf before you’d get a decent enough crop to harvest, making it the most precocious of all commercial tree fruit or nuts.

There is no understating Anderson and Puryear’s contributions, Fanucchi says. “There was a while there where it looked like the pistachio industry might not make it because of verticillium wilt. But Pioneer Gold saved the industry,” he says. “There’s no doubt in my mind the industry wouldn’t be where it is today without Pioneer Gold.”

Fanucchi, who estimates he’s been involved in planting about 45,000 acres of pistachios in his career, says the two men’s impact went beyond the resistant rootstock and came at a critical time.

“Integrity meant everything to those two guys,” he says. “They would give growers trees for replants, even when it was the grower who messed up. Everybody was figuring out how to grow these trees, including us.”

‘GROWING AN INDUSTRY’

One of those young people growing with the industry was Brian Blackwell, who started working at Pioneer Nursery when he was just 14 years old. Like Fanucchi, he was quickly impressed by his two bosses.

“Their interest was not just in growing trees, it was growing an industry,” he says.

Pistachios were different from other tree fruits and nuts in so many ways, not the least of which was the fact it was essentially a brand-new crop in the U.S. There was a feeling of collegiality, and as a young man, he was blown away by the many meetings in which top growers talked about their “secrets,” such as fertility regimens, etc. Because of them, it became common knowledge, for instance, that boron is critical — pistachios thrive on it.

“I just think there was a little bit more camaraderie because we went through that infantile state together. What also makes it different is the original growers of other crops aren’t here anymore. But Ken, Carl, etc. are still around. They have shown us that the goodwill, the camaraderie, is good for everybody,” he says. “It’s incumbent on us to make sure we continue with that same zeal for helping our fellow growers out. I knew Corky 50 years, and Corky would jump into anyone’s field at any time and help them out with any problem they may have had. That goes a long way with growers.”

Blackwell later worked for industry giant Paramount Farming (now Wonderful Pistachios & Almonds) and even returned for a second stint at Pioneer Nursery before starting his own management company, Blackwell Farming Co. Through the years, he’s served a number of industry associations and was chairman of the California Pistachio Commission in 2007 when it was dismantled because Paramount withdrew its support, arguing it was a “freedom of speech” issue.

Today, according to industry estimates, Wonderful Pistachios & Almonds is responsible for about 12% to 15% of the state’s production, but its impact is even greater, marketing an estimated 55% to 60% of the total. The pistachio industry is unusual among fruit and nut crops, as just seven processors are responsible for 98% of the volume.

MARCHING FORWARD

Without a marketing order, and without the support of the industry behemoth, Paramount, Blackwell says a lot of growers were worried about the future. But they got together to form a voluntary organization, Western Pistachio Growers, and installed Richard Matoian as the first president. The name later changed to American Pistachio Growers (APG) to better reflect the nature of the industry to the rest of the world, says Matoian, who remains in charge.

That world view is critical because more than 70% of the pistachio crop is exported. Consumption is growing, especially in such key markets as China and India. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, even despite increased tariffs, the industry was sending record numbers of nuts into China. They got some luck there, Matoian says, as when the tariffs were originally implemented, the Chinese couldn’t look elsewhere. Iran had no crop because of a terrible freeze.

Iran is the U.S. industry’s only big competitor, and while Iran used to dominate, the U.S. surpassed the Middle Eastern country in 2008, and that’s before the considerable U.S. plantings of this millennium even came into production. Iran still has 200,000 more acres, but a lot of that is farmed as bushes, not as trees, and they have even greater water problems than California, losing 20,000 to 40,000 acres each year to desertification.

The U.S. faces problems of a different nature. With nearly one-quarter of its acreage yet to come into bearing, and more being planted every year with virtually no acreage coming out, APG would appear to have quite a daunting challenge, as much larger crops loom in the future.

“Or quite an opportunity,” Matoian shoots back. “And the opportunity we have is so many new consumers are waking up to the nutritional value of tree nuts. Pistachios are undervalued compared to almonds and walnuts. People know about them, but they’ve thought of pistachios as a salty snack. They have just been identified as a complete protein, and few foods can match that — having all nine amino acids.”

Matoian says when he joined the industry years ago during tough times, he certainly wasn’t thinking of hitting a billion-pound crop. Blackwell and Fanucchi say they never dreamed of it. But Puryear, the man who had never eaten a pistachio, says it’s no surprise: “It’s a hell of a good product!”