Avoid Food Safety Problems

Almond growers will do pretty much anything they can do to increase their yields. And why not? It’s not like growing apples or winegrapes where they get paid in large part based on quality. No, barring any bad quality problems, almond growers are paid pretty much on quantity. But that can be a problem, says Bruce Lampinen.

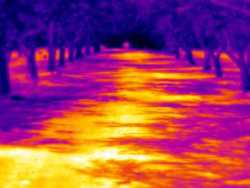

Heavy-yielding almond blocks are also heavily canopied blocks, says Lampinen, a University of California integrated orchard management/almond and walnut specialist. “Orchard management can impact food safety risk in almonds,” he says. “Heavily canopied orchards likely increase food safety risk due to wetter, cooler conditions on the orchard floor.”

The problem with stockpiling almonds is that from a pure food safety perspective, you wouldn’t do it at all. But as Bruce Lampinen notes, hullers will require stockpiling to be able to process large quantities of nuts and also because it makes the nuts’ moisture content so much more uniform. “It’s much more practical,” says the University of California integrated orchard management/almond and walnut specialist, “you have to stockpile.”

Here then, are some stockpiling tips to keep in mind to help ensure you meet food safety guidelines:

1) Make sure nuts are adequately dry before stockpiling. Incoming moisture content is key. Do not stockpile if either the hull moisture content exceeds 13% or the kernel moisture content exceeds 6%.

2) Growers should sample their moisture content. There are now hand-held devices available for growers to sample the moisture content of their crop in the field. Sample nut moisture content in a systematic way across the orchard before beginning harvest, making sure to sample nuts from both the biggest and smallest trees.

3) Besides food safety considerations, sampling is a good idea because many growers have orchards that are too dry. If the almonds are too dry they don’t slice and dice properly; they tend to shatter. Of course you want to produce an almond that’s safe to eat, but you also want to produce an almond that is sought after by food processors, etc.

Add it all up, and Lampinen concludes that any orchard producing above 3,500 kernel pounds per acre likely has an increased potential for food safety related problems. For the past few years, Lampinen has been studying the relationship of how much sunlight hits the floor of an orchard, how that can impact potential productivity, and in turn how susceptible the crop is to food safety pathogens. There are some direct correlations.

Sunlight = Almonds

For example, Lampinen has found, using a mule light bar device, that almond production potential is about 50 kernel pounds of almond for every 1% of midday incoming light intercepted. In other words, there’s no doubt that the greater amount of sunlight intercepted by the leaves, the greater the yield potential.

At about 70% light interception, sunlight hits about 30% of the orchard floor, and there seems to be a demarcation point. If you go above 70%, the almonds get difficult to dry. “Growers want to go to 90%, but that’s not necessarily a good trade-off,” he says. “Even with pasteurization you’re going to have a much higher risk of salmonella. There’s definitely a trade-off there.”

There are some orchard design steps growers can take to help ensure food safety. For example, Lampinen has found that hedgerow planting tends to lead to dense shade under tree rows and may increase food safety risk. More conventional tree spacing leads to more varied light/temperature patterns across the orchard floor.

Don’t Go West

Also, if you plant an orchard with an east/west orientation, you will have more drying problems. A north-south orientation is best. As the sun angle gets lower in that type of orchard, you can still get light in the middle of the row.

The spacing depends so much on how you manage the water, says Lampinen. In years four, five, and six, if the canopies are getting too crowded, you might want to use deficit irrigation to slow them down and try to minimize future excessive shading. “With experience you can do a pretty good job,” he says, “especially if you use plant-based measurements, such as with a pressure chamber, to assess actual levels of tree stress.”

The best approach is to plan an orchard where you get 70% light penetration, says Lampinen. Growers will still get profitable yields, and can minimize food safety risk. “Growers always seem to err on the side of (too much) density,” he says. “You’re better off assessing your orchard planting design and canopy structure in relation to your food safety risk.”