Using NASA In Nut Production

Nut growers will soon be among the most technologically savvy agricultural producers, thanks in part to a grant from USDA’s Specialty Crops Research Initiative (SCRI) that will allow researchers at three prominent universities to use NASA satellite imagery to study nut production management issues. The grant for $870,000, given to researchers at New Mexico State University (NMSU), University of California-Davis (UC-Davis), and Texas A&M University (TAMU), will help fund research in irrigation and nutrient management, among other potential production issues.

Texas A&M University and New Mexico State University will focus on pecans while UC-Davis researchers concentrate on walnuts and almonds. Each university is developing similar models and websites to address irrigation and nutrient management issues. The researchers say satellite imagery will one day help growers predict yield potential and timing of key events in plant life to target irrigation and fertilizer application schedules and predict when pest and disease problems might emerge.

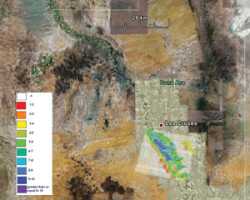

“One of the challenges facing growers is the ability to target management to address the variation in productivity that exists in fields,� says Patrick Brown, a professor of plant nutrition at UC-Davis. “If growers manage the whole field as a single unit, with everything getting the same water and fertilizer rates, then there will inevitably be over-fertilization of some sections and under-fertilization of others. In its simplest form, satellite imagery will allow growers to see this variability and to move toward more targeted and precise management.�

|

|

Another critical element to using NASA satellite images to study orchard health is to catch any water stress or nutrient deficiencies before they become a problem, rather than relying on broad climate data to determine when to schedule irrigation and apply fertilizers, says Richard Heerema, NMSU Extension pecan specialist.

“Satellite images can detect stress levels when they are still low and not affecting yield, whereas growers may not be able to see these symptoms during a physical visit to the orchard,� Heerema says. “The potential is there for even detecting pest pressure and measuring their effects on the orchard for a few pests, such as aphid infestation, which stresses the actual tree. Other pests, like pecan nut case bear, which is a kernel-eating pest that does not affect the tree’s health, isn’t something satellite imagery would be able to detect.�

While satellite images will not replace scouting, it gives a larger view of crop status with proper analysis. This, coupled with growers’ knowledge of their crops and soils, will provide a better basis for management decisions and crop response, Brown says.

According to Mike Whiting, a post-doctoral scholar in the Department of Land Air Water Resources at UC-Davis, satellite imagery “gives a synoptic view of orchards that is sensitive to near-infrared light levels, and beyond into the thermal region of light. Manipulating this digital data can enhance the images to develop maps of the relationships to nutrient and soil variation that change plant canopy and water status,� he says. “The tools through our Internet site will provide color and color infrared images, as well as analyzed image maps of their orchards for viewing and downloading.�

Researchers need to make the comparisons between what is being measured on the ground and the satellite images before growers will actually be able to use the technology themselves, Heerema says.

“We have good ways of measuring stress management from the ground and we also have methods in place for making measurements from satellite images, but actually ground-truthing these satellite images, relating those images to actual tree performance, yields, and photosynthesis, and collecting data will take a few years,� he says.

Empowering Growers

Ultimately, the goal is for growers to be able to access satellite imagery of their orchards, from anywhere, at any time, Heerema says. “The beauty of the satellite approach is that any growers, anywhere, would be able to access data from their own computers to get the big picture of their own orchards very easily and whenever they want it,� he says.

Initially, this wealth of information will come at a cost; however, as satellite image technology is developed, costs to growers will continue to fall, says Brown, who uses Mapquest as an analogy. The GPS-driven software that allows the public to access easy driving directions was once only available at great expense to the Army, he says, and now is free to everyone.

“The first loop of this orchard imagery will be similar, more expensive in its first release and rapidly becoming very low cost or free,� he says. “We will also reduce the cost of early use by offering first step ‘simple’ solutions, such as a text message to a grower indicating the current water and nutrient demand of his orchard, based upon averaged data. These first steps will nevertheless be a great advance over the very generic decision-making process currently in practice.�

Whiting adds the UC-Davis website will allow growers to log on to a Google Earth-like application to select their orchard to view and download images, such as daily evapotranspiration, annual winter chilling, and predictions of yield, nutrient, and water requirements. An archive of data including satellite imagery and interpretations, as well as all primary data, will be available.

“The general acceptance of this type of browser interface demonstrates the easy access,� Whiting says. “Specific orchard information, such as yield and management practices input by the growers, will be incorporated in future versions. This information will improve the models and help individual growers adjust their forecasts based on the model results.�