How Precision Agriculture Can Help Growers Know Their Crops Better

Precision agriculture can be a nebulous term for many growers, but at its core, it’s just about getting a more accurate picture of what’s going on so you can farm accordingly. Being able to pinpoint weak spots in your orchard and correcting them, for example, is one way to give your yields of target fruit a boost.

Being precise requires more data. In fruit and nut growing, that means taking pictures — lots of them. However, the companies selling precision agriculture products collect those images in different ways, even on different aspects of the orchard.

In talking with researchers, three companies stand out in this arena for their distinct approaches: FruitScout, Green Atlas, and Hectre. All started on apples, though since then all have branched out into other fruit and nut crops.

Two of the three companies are from “Down Under,” which is not really a surprise as many of the precision agriculture companies were founded outside the U.S., in large part because of the old saying, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” Many countries around the world faced labor problems years ago, well before U.S. growers began acutely feeling shortages, and began more intensively concentrating on mechanizing fruit growing to cut burgeoning labor costs and improve profits.

MANUFACTURING MODEL

The Founder of FruitScout, Matt King, believes the principles of a sensor-driven manufacturing plant transfer nicely to predictable fruit growing. Several years ago, the aerospace engineer, then at Boeing, was telling his wife about the sensors he managed at all of Boeing’s factories, how they tracked components end-to-end through the manufacturing process.

“My wife asked, ‘Can you do that for my greenhouse?’” King says, who then had an inventor’s “Eureka!” moment.

King co-founded a Seattle company based on the idea, iUNU, which focuses on precision greenhouse management by employing sensors throughout, following the modern manufacturing model. When Washington apple growers heard about what they were doing and inquired, the idea morphed into FruitScout. King patented the technology in 2019, on which the Yakima, WA, company is based.

“An operational visibility perspective really guides the company,” King says. “Growers have been implementing crop load management practices, but they are short on data; they just didn’t have enough good data to do precision crop load management.”

Because King believes capturing data is the key, he has tried to make it as easy as possible for growers. All that’s required of the grower to collect data is to snap photos with their smartphone. Besides the FruitScout app, that’s the sum total of the necessary equipment.

Growers begin by determining the optimal capacity of fruiting trees by taking pictures of the trunks, then managing to those targets through the rest of the season. Data from FruitScout informs how much to prune and thin to stay on track for optimal yield.

“We’d say it’s magic, but it’s really just computer vision and a patented AI (artificial intelligence) algorithm,” he says. “It’s based on the precision crop load management model developed by Cornell University and the University of Massachusetts, who estimate growers can get $5,000 to 10,000 more per acre (in profit).”

Gathering data with FruitScout is much faster, according to King. For example, he says it would take 250 hours to hand-count blossoms on 1,000 trees, something FruitScout can do in less than an hour-and-a-half and with more precision.

At fruitlet thinning, FruitScout also provides a more efficient way to predict fruit set, relying on a random sample of 500 fruitlets vs. measuring the exact same fruitlets over time. The method, proved out by Todd Einhorn of Michigan State University, is a practical application of the Fruit Growth Model pioneered by Duane Greene at the University of Massachusetts.

Growers will typically photograph the random fruitlets after chemical thinner application, then again four to five days later. FruitScout will predict your fruit set from the image analysis, giving you ample time for another round of thinners if required. No need to keep track of and revisit the same fruitlets for the analysis.

“They can automate what they’re doing manually; that’s the only change in their process,” King says. “The process scales, providing way more data than they could collect by hand, and they can use that data to optimize their crop load end to end, increasing the predictability of yield throughout the whole growing cycle.”

SPEED TO BURN

Green Atlas acquires images in a very different way, by speeding through orchards in an all-terrain vehicle and shooting huge numbers of photos. And the Australian company does mean speeding, traveling through almond orchards at more than 30 mph, says Co-Founder James Underwood.

“These cameras are whipping through the trees and bouncing around, and it doesn’t hurt the quality of the images one bit,” he says, marveling at how the technology has improved over the past decade. “With apples we go slower (about 12 mph) because the row spacing is narrower, and because the closer you are, the harder it is to get as many images — especially because you often have bumpier orchard floors. But we can go faster if you want a quicker shot with less data.”

Underwood and Co-Founders Steve Scheding and Peter Morton met doing grower-funded research at the University of Sydney. They were looking into precision agriculture to learn what’s possible.

“We started 10 years ago, before camera technology was used in ag and before it was known if they would apply to ag in general, and orchards in particular,” he says. “We started learning this actually does work, and we were getting good feedback from growers. But they kept asking, ‘When will it be commercialized?’”

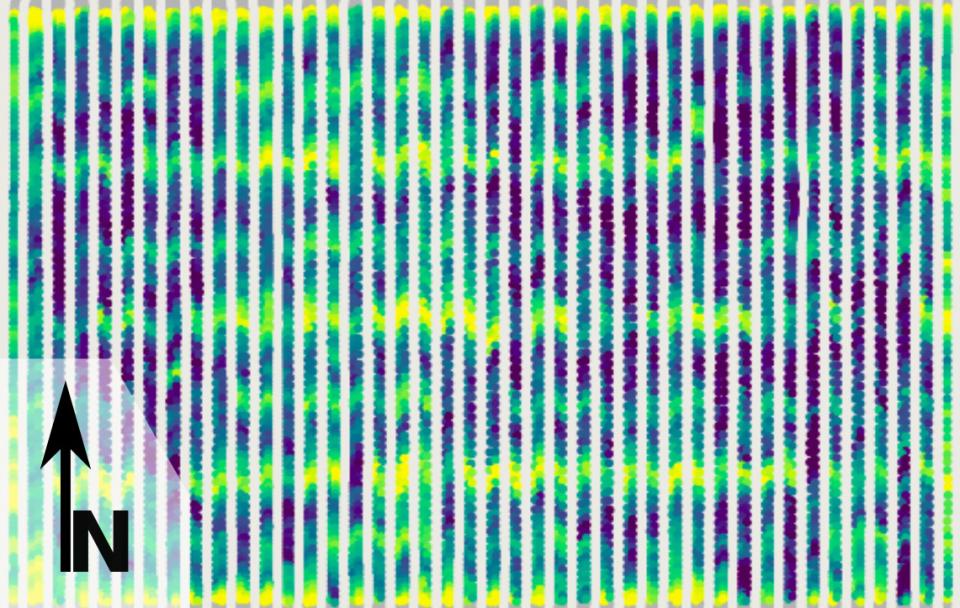

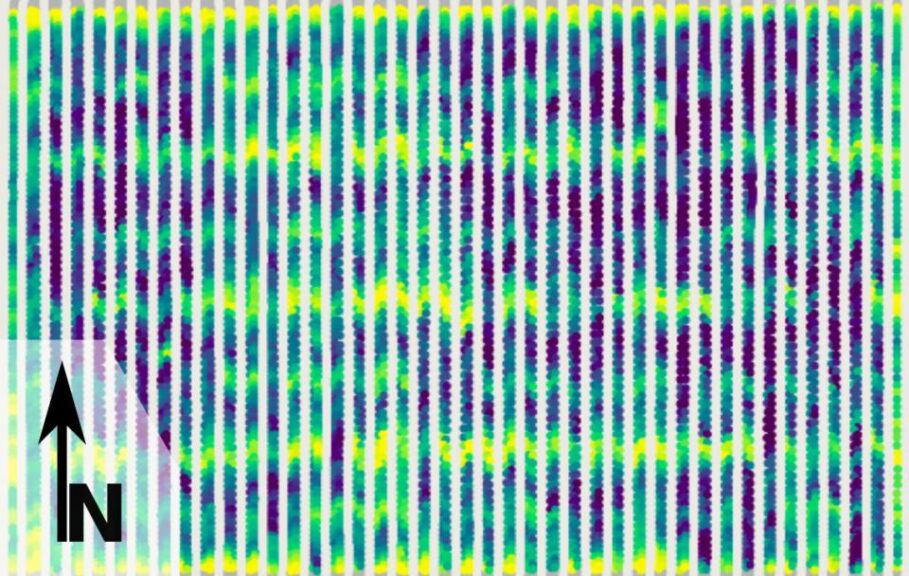

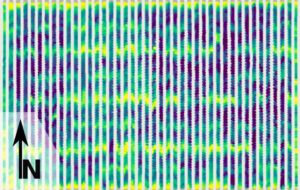

The answer was 2018, when they developed Cartographer, the technology the company had been founded upon. Cartographer is a combination of hardware and software that allows flower and fruit counts to be quickly and accurately mapped over entire orchards. It also utilizes LiDAR (light detection and ranging) to measure tree canopy geometry throughout the orchard. Combined, this produces high resolution AI-assisted mapping, allowing growers to take a closer look — right down to every tree — to help manage the life cycle from flower to fruit.

The information is critical for growers, Underwood says, so they can know the relative performance of different blocks, comparing overall yield and the evenness of the distribution within each block. They can then determine optimum management zones to address variability and achieve consistency every year. Growers can also know how well their thinning program worked and then adapt it for the next year.

“It’s like a 3-D camera measuring the geometry of the trees — it’s the same technology used in driverless vehicles,” he says. “You can also understand the light interception of the trees, a key piece of data in itself.”

Tying all that data together allows growers to make the best decisions, he says. At its most rudimentary level, a grower can take all the maps and get a simple pdf report, which they can print and check the orchard. But most prefer to load the information onto their smartphone, walk the field as necessary, and overlay what they do on that map. This allows growers to give precise instructions on thinning to their workers or, to save even more labor, they can load maps right into their variable rate sprayers, root pruners, etc.

“Good farm managers already sample different trees. But that takes labor, and it’s not uniformly consistent,” Underwood says. “One hundred trees out of 10,000 could be misleading because there could be a problem one row over. Our mapping system is a way to cover that, because you scan every single tree in a very cost-effective way.”

BIN-CENTERED TACK

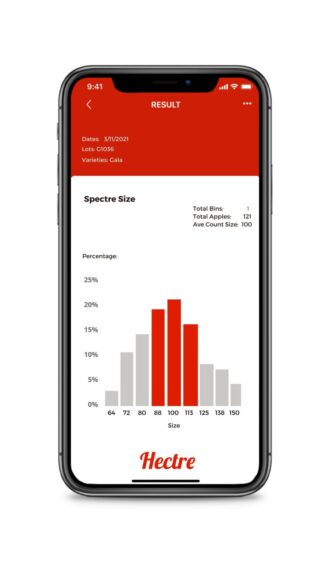

Hectre — which was founded in New Zealand, thus the name — takes a completely different approach to collecting images with their Spectre technology, shooting photos of apples in the bins to get an accurate picture of what’s coming off the orchard. If that sounds like it would be valuable to packer/shippers, it is, as initially their main sales were to packer/shippers, says Hectre’s Business Development Manager Elizabeth Hargrave.

“But now in year two, more growers are approaching us. They’re using Spectre to understand what’s coming out of the orchard,” she says. “Integrated grower/packers really love it. But independent growers do too, especially if they’re shipping to multiple warehouses, because they want more data, they want it faster, and they want it before it comes back from their four or five warehouses. And they want all the information in one place.”

Actually, Spectre was conceived after a discussion with a grower, Hargrave says.

“We got this idea from a New Zealand grower who said ‘I have all these pictures on my phone. I should just be able to take a picture of a bin of fruit (to collect data),’” she says. “It’s amazing how many growers have told me, ‘I had that idea; why can’t I just use this picture on my phone?’ It’s been a nice affirmation of what we’re doing.”

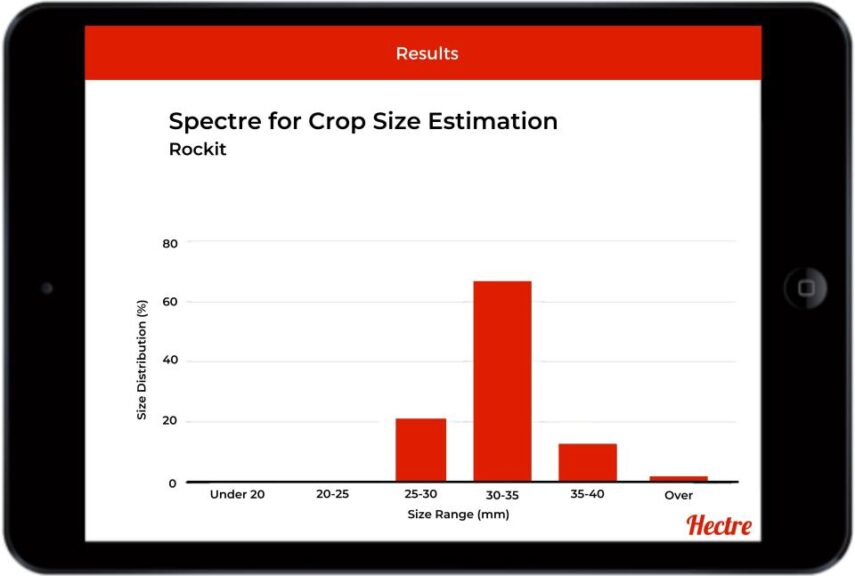

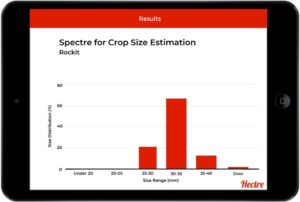

Postharvest, Spectre uses computer vision and machine learning to assess apple size — and color — and then uses algorithms and statistical tools to estimate the size distribution of an apple bin in real time, all from one click on a tablet or smartphone. Hectre has found that in comparing their estimates with packinghouse graders, they are 95% accurate — a far better estimate than can be achieved by growers’ traditional methods, counting limited samples.

“The more bins you scan the better the sizing,” she says. “You only need a few images to get those top three sizes growers generally want.”

Besides apples, Spectre is being used in the citrus industry. But they’re also working with other fruits, currently in final testing for cherries, with pears to follow.

Hargrave, who is based in Yakima, WA, says Hectre is also going to estimate preharvest. They picked what would seem to be quite a challenge, working with New Zealand grower Rockit Global, the originators of the ‘Rockit’ apple, doing sizing preharvest. The club variety, a cross between ‘Gala’ and ‘Gala Splendor’, is about the size of a golf ball and is often marketed in clear tubes.

Many growers aren’t yet familiar with all the new technology, so Hargrave believes it’s the simplicity, and ease of use, that plays a huge part in Spectre’s success.

“Whatever technology we put out, we try to ensure it’s the simplest version it can be,” she says. “Most of it comes down to a better understanding of what’s going on in the orchard. There are so many decisions resting on that one moment in history.”